Feb. 3 2023 Hello , On this day in1945, United States army forces stormed the gates of Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila, Philippines, freeing army 78 nurses who'd been imprisoned by the Japanese for three years. Marking February 3, we remember the bravery and endurance of these women who survived the brutal circumstances that killed so many others. From the women's stories we learn how they nourished the will to live, what kept their minds strong as their bodies weakened from starvation and what really happened the day liberation finally came. But first, my thanks to Clare who wrote to ask about what happened when the nurses finally came home. Did they suffer PTSD like many soldiers did? I'll discuss that at the end of today's feature story. And now...imagine the dark of night, the sound of bombs exploding in the distance, erupting flame and the noise of planes overhead. You're huddled in your room, crowded with the other prisoners hoping the US will gain control of the city and set your free. Fearing if it takes one more day, you might die, starvation taking you before

the walls come down.

One Woman So Tense She Spiked a Fever

Back in the states, families of the POWs followed news reports of troop movements in the Philippines with a mixture of hope and dread. After the first news flash from Manila, Emma Lewey, in Dalhart, Texas sat next to her radio until midnight hoping for some word of her daughter, Army Nurse Frankie Lewey. So great was her suspense, she ran a fever as she maintained her vigil. Her phone rang again and again as friends and family called with the news that

American nurses were among those liberated at Santo Tomas. But there was no direct word identifying Frankie. She hadn't heard from her daughter in the last two-years. Mrs. Lewey’s was almost at the breaking point when her granddaughters phoned from Oklahoma City to say they'd heard the list of nurses. Frankie was alive.

US Army Nurse Frankie Lewey, February 3, 1945, one of the nurses still strong enough to tend soldiers wounded in the battle to liberate the prison camp.

Twelve hours before, Frankie had eaten the only food she could find, a bit of moldy rice. When Japanese soldiers had rolled barrels of gasoline under the central staircase in her building, she heard the whispers. The Japanese planned to torch the camp, leaving no evidence the prisoners had been there. Frankie was so tired she barely cared. Her bones ached. Her once thick red hair was falling out. Malnutrition had weakened until she could hardly stand. With no warning the electricity cut out, plunging the camp into darkness. Shrill voices shouting in Japanese sounded from outside the building. Rifle and machine gun fire popped. Loud. Close. Flares shot into the sky outside the front gate. Frankie stared into the darkness, her heart beating

wildly. The nurses clutched at each other with desperate boney fingers. A rumbling—a mechanical, earth-shaking growl—filled their ears. The smell of gasoline…a

sudden glaring light…a thundering crash…a rolling shudder. Friend or enemy?

An armored monster smashed through the front gate. A powerful searchlight beamed from the mechanical beast—grinding straight toward them—the stopped just shy of the front doors. Shadowy figures dismounted.

“Howdy, folks!” Unmistakably American.

Screaming, shouting, crying, people leaned from the windows. Inside the building prisoners went berserk with joy, stumbling down the stairs, spilling into the plaza, surrounding the soldiers. Some prisoners fainted to the dirt; others prayed, hugged,

and kissed and others mobbed the soldiers.

Someone in the crowd started to sing God bless America…” A thousand voices joined, and the song swelled and rose. Former prisoners cheer their liberation in front of the camp's main building.

Like Frankie, nurses who were strong enough worked through the night caring for battle casualties and continuing to nurse civilian internees in

the camp hospital they had organized three years before. One nurse, Rita Palmer was a patient in the hospital herself, but jumped up

to help the other nurses. This esprit de corps had been an important factor in the nurses' survival. Strong friendships had developed between the women and these bonds helped keep up their courage. In addition, continuing their vocation as nurses gave them a purpose. Though sick and weak themselves, taking short shifts at the hospital caring for others gave them a reason to leave their beds, a reason to force their weak and aching bodies across the camp to the hospital. A young civilian girl in the camp, Sascha Weinzheimer, would have died if not for one of the nurses, Denny Williams, who sat up with her all night after an emergency tonsillectomy. Decades later, Sascha told me, "I was scared because they gave me last rites, I couldn’t stop bleeding. As a Catholic I knew what last rites meant. I lost so much blood

they had to give me a direct transfusion, all I remember was Denny staying with me." Ten-year-old American Sascha Weinzheimer and her brother, Buddy, in a photo staged by the Japanese to suggest prisoners are well treated, 1943. Photo courtesy Sascha Weinzheimer.

The strong leadership of the Army Nurse Corps commanders proved to be essential in the nurses' survival. They were no longer at their posts treating US military patients, but when they were assigned to scrub toilets, their commander, Major Maude Davison, stood up to the Japanese Commandant, insisting her nurses be treated with dignity and allowed to practice their profession. Major Davison was a World War I veteran and a formidable woman. She was determined her nurses remembered they belonged to the US army and disciplined them accordingly. American troops liberated the Japanese Santo Tomas internment camp in Manila, Philippines, but for these women, it still was washday.

It was

nearly two weeks after the gate came crashing down before the army was able to evacuate the nurses from the camp, which remained in a war zone. But they were the first former prisoners to leave Santo Tomas. Former POW nurses smile leaving Santo Tomas Internment

Camp. US Government photo.

The morning of

February 14, the nurses climbed into trucks, a crowd of their fellow prisoners and American GIs gathered in front of the Main Building to send them off. Waving, they passed

through the iron gates of Santo Tomas onto España Boulevard, headed for a makeshift airstrip and their flight to freedom. Former POW nurses pose before boarding their flight out of Manila. US Governmet photo.

Their commitment to a purpose, strong bonds of sisterhood and identification with

something larger than themselves serve as an example as we face our own challenges. Which for most of us are far less grueling than spending years as a prisoner-of-war. However, the burdens we carry in our particular lives, the pain of our losses and the struggle to do good work and love well, none of it is easy. May the extraordinary example set by these women inspire us.

Like my article today? Please share:

And now for the

question about whether the nurses experienced PTSD. Homecoming proved challenging for many of the nurses. Due to disease and malnutrition, some had life-long health issues. There's more on that in my book, as well as many other difficulties they faced. The women came home with one simple desire—to get on with their lives. Their instincts were to forget the brutality they had seen and endured, the long months of psychological strain and abuse, illness and starvation. The diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder was two wars and a generation yet to come. But most of them had the symptoms. Mildred Manning, the one nurse still living in 2012, told me her the trouble started almost immediately. "I just didn’t know it at the time. We all put on a lot of weight right away and I was having dry skin and depression and a lot of things like that. I went to the doctor and told him all my troubles. And he

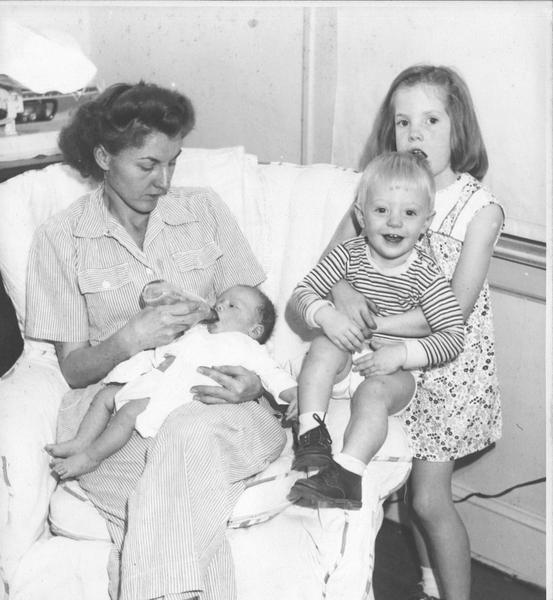

said, well, sweetie there’s nothing wrong with your appetite is there? I never went back." Former US Army Nurse and POW Mildred Manning and her three children c. 1955. Photo courtesy Mildren Manning.

When I interviewed Mildred, she was 98 years old and hadn't recovered from the effects of her wartime years. Because of the crowded conditions at the prison camp, she avoided going anywhere throngs of people congregated, like

shopping malls. She told me, "If somebody comes in the room and I don’t know they’re there and they tap me on the shoulder, I’ll jump out of my skin. Still a lot of anxiety left." I think the issue of nurses and post-traumatic stress needs close attention as we move on from the Covid 19 pandemic. Medical staff who faced over-crowded hospitals, long hours,

not having equipment they needed and caring for a record number of patients dying without their families, surely face lingering mental and physical stress. I'll be writing you again with more stories from the former POW nurses in the next two months as we mark several more important anniversary dates.

Follow me on social media

Read a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this

e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help

students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this

newsletter. |

|

|