March 10, 2023 Hello , The United States military faced a severe shortage of pilots at the beginning of WWII and leaders took what they thought was a gamble, allowing women to fly noncombat missions. When the call went out, more than 25,000 women applied. From those, roughly 1,100 made the cut, forming the volunteer Women Airforce Service Pilots. Better known by their

nickname WASPs, these airwomen freed male pilots for combat overseas. Though desperately needed, 1940s attitudes about women made their jobs tougher. In ferrying aircraft from location to location, women aviators occasionally had to touch down to use a restroom before reaching their destination because the

military aircraft they ferried had no toilet facilities for females. For a time, WASPs were grounded during their menstrual periods because male commanders believed airwomen were “less efficient during menses.” Some restaurants refused service to WASPs because

they were wearing pants. The women pilots earned only two-thirds of what male pilots earned, and their age range for service was lower “to avoid the irrationality of women when they enter and go through menopause.” For more on the story, please welcome Historian Norm Haskett, whose website The Daily Chronicles of World War

II is likely the most comprehensive WWII site on the internet.

The WASP program was born in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor when the U.S. military experienced a severe pilot

shortage. Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran, a hotshot woman pilot competing against the likes of Amelia Earhart in 1930s air races, wrote to another woman who had famously taken flying lessons, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Below: Jacqueline (Jackie) Cochran (1906–1980), founder of the Women’s Flying Training Detachment in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk

Mrs. Roosevelt soon became a vocal advocate of making women pilots eligible for military service. “Women pilots . . . are a weapon waiting to be used,” the First Lady wrote in her newspaper column, My Day. Cochran’s proposal to Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Chief of U.S. Army Air Forces, along with another proposal by ace pilot Nancy Harkness Love to Arnold, were separately put into

action in September 1942. The women’s proposals had the same goal: allowing qualified women pilots to perform noncombat missions to free up scarce male aviators for combat roles. Nancy Love’s Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron (WAFS) was tasked with ferrying

newly built aircraft from factory to military bases. Jackie Cochran’s Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) was tasked with training more women to ferry the aircraft to end-users. In August 1943 the two organizations were merged to become the WASP under Cochran.

Four WASP pilots at the four-engine flight school at Lockbourne Air Force Base, Ohio. They are

Frances Green, Margaret (Peg) Kirchner, Ann Waldner, and Blanche Osborn.

WASP recruits had to have a high school diploma, be between 21 and 35 years old, be in good health and in possession of a commercial flying license, have 35 hours of flight time, and

stand at least 5 feet 2 inches (157cm) tall before their application could be accepted. Over 99 percent of the trainees were white women, one was Native American, two were Hispanic, and two Chinese American. A few applicants were African Americans and made it to the final interview stage, only to have their applications rejected because of their

race. After completing four months of training in flying “the Army way” by U.S. Army Air Forces instructors, the pilots earned their silver wings and joined the first all-women units to fly American military aircraft. WASP pilots relax on an unnamed air force base (probably Lockbourne Air Force Base in Ohio), where they trained to ferry four-engine Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses.

Although attached to the United States Army Air Forces, these pioneering women aviators were actually civilians who were federal civil service employees and therefore had no military standing. Oddly, these women were pretty much forced to wing it on their own, first starting with paying for their own uniforms, room and board, and pilot training and ending with paying their way home after discharge or for their own funeral, burial, and coffin upon which no American flag could be draped because the deceased (38 WASPs during the course of the war) were not military personnel. Four WASPs view an aerial chart on the wing of a North American AT-6 Texan trainer.

Trainer aircraft were used to tow trailing cloth targets and help train ground antiaircraft gunners for combat. Sometimes steel tow lines were severed, the targets floating to earth, and some trainer aircraft were pierced by errant bullets. This was about as close to being in combat as a WASP pilot ever got. About 300 WASPs were tasked to train antiaircraft ground troops. Training consisted of towing a cloth target on a long metal wire attached to the tail of their

trainer aircraft so that ground troops could practice shooting at the target using real ammunition. It was dangerous work. Other sets of WASPs—those attached to the Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron—were stationed at 122 air bases across the U.S. in six ferrying

groups. They flew over 60 million miles, delivered 12,652 aircraft of 78 different types from manufacturing plants to end-users, and transported every type of cargo. WASPs in cadet uniforms standing outside with a male officer and Jackie Cochran, who is seen in a dark dress. University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; courtesy of National WASP WWII Museum.

Before the program was discontinued at the end of 1944, WASPs flew 80 percent of all ferried military aircraft

(the women flight-tested each one first) and freed about 900 male aviators for combat duty.

Sadly, these veteran airwomen who had sacrificed and achieved so much during America’s wartime hour of need were prohibited from piloting aircraft in the postwar armed

services. They worked hard to be recognized and rewarded for their wartime heroism and achievements, so quickly forgotten in peacetime as the nation struggled to “return to normal.” They continued to work hard for decades fighting gender discrimination and prejudice in the U.S. military and negative public opinion. To the final graduating WASP class on December 7, 1944, Jackie Cochran accurately predicted: “I think it’s [your service] going to mean more to aviation than anyone realizes.” Jacqueline Cochran reviews a line of women pilots who were nicknamed “Woofteddies” based on their unit’s acronym. Cochran is accompanied by a U.S. Army Air Forces officer at an unnamed airfield. Cochran was later a sponsor of the Mercury 13 women astronaut program (1959–1962).

Beginning in the 1970s the shroud of obscurity surrounding the WASP was lifted by the federal government release of WASP records. Dramatized stories on television, in feature films, in dozens of books, and several high-level award ceremonies, including awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to WASP women in 2009, drew significant public attention. Today, the granddaughters of these pioneering airwomen proudly serve in air wings of all branches of the U.S. armed forces and have done so since 1973–74 (Navy and Army), 1976 (Air Force), and 1977 (Coast Guard). Thank you so much for your guest article today, Norm! How many years did it take for these incredible women to be acknowledged and honored for their flying abilities and contributions to the war effort just like their male counterparts? Norm has a great article and photos on that at his website today.

Like Norm's article today? Please share:

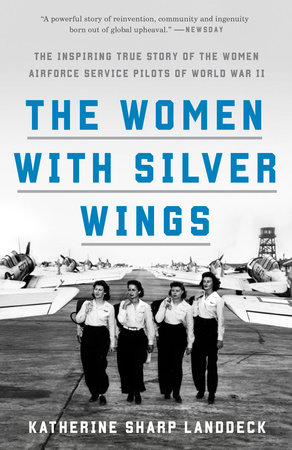

And there's book! Author Katherine Sharp Landeck says the women pilots were cast aside in 1944, before the war even ended. "It was a very controversial time for women flying aircraft.

There was a debate about whether they were needed any longer," Landdeck says. As the massive war effort started to wind down, personnel had to be cut. "It was unacceptable to have women replacing men. They could release men for duty — that was patriotic — but they couldn't replace men," Landdeck says.

Follow me on social media

Read a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can

unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|