March 17, 2023 Hello , Happy St. Patrick's Day! I didn't celebrate this holiday seriously until I met my sweetheart Michael Farrell, a man very proud of his Irish ancestry. We celebrated our 20th anniversary with a trip to

Ireland, where I took my first peek into Irish history, learning of the brave women who risked their lives fighting for equality in Ireland's famous Easter Rising. Michael Farrell near the Cliffs of Mohr.

Equality? You might ask, wasn't the Easter Rising a rebellion against the British? A quest for Irish independence? Intersectionality is the term we use today to describe the connection between seemingly disparate political issues, but Irish women were living this ideal more than

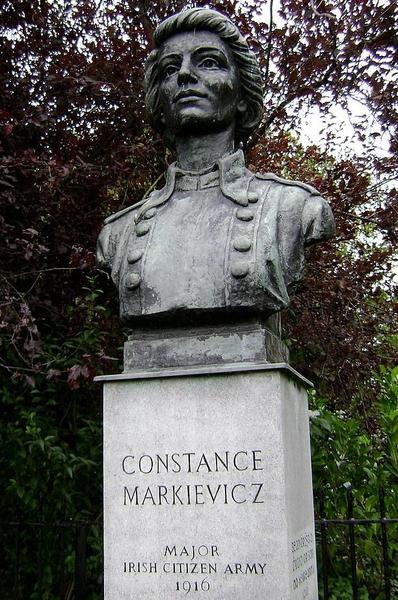

a century ago when 77 of them were imprisoned and one sentenced to execution after taking up arms against the British. The most well-known, Countess Constance Markievicz, had courage in abundance, a heart for the poor and a flair for the dramatic, famously kissing her revolver before giving it up to a British officer when she and the other rebels were forced to surrender.

No Luck. She was All Spunk!

On my Ireland trip, I visited the cell in Kilmainham Goal where Constance Markievicz was held after her arrest, and the spot where 16 of the ringleaders of the Easter Rising were executed by firing squad and Constance narrowly escaped with her life. Yard at Kilmainham Goal with cross marking location of executions, Dublin.

Constance née Gore-Booth was an unlikely revolutionary, born an Anglo-Irish

aristocrat, raised on a wealthy estate in Sligo, trained as a landscape painter in Paris where she met and married a Polish count, Casimir Markievicz. Returning to Ireland, living by chance in a rented cottage she discovered literature promoting Irish independence, yes, the power of the written word thrust her into a life of activism.

“The first step on the road to freedom is to realize ourselves as Irishwomen – not as Irish or merely as women, but as Irishwomen doubly enslaved and with a double battle to fight,” she wrote in 1909.

One of her first crusades helped defeat Winston Churchill's bid for a British Parliament seat. He'd spoken out against women's right to vote. “[Women's suffrage] was one of the first things I worked for since I was a young girl. That was my first bite, you may say, at the apple of freedom and soon I

got to the other freedoms – freedom to the nation, freedom to the workers. The question of votes for women, with the bigger thing, freedom for women and the opening of the professions to women, has been one of the things that I have worked for.” Constance worked with the Cumann na mBan, a revolutionary women's movement, Sinn Féin (Irish republican and democratic socialist party) and became a commissioned officer in the Irish Citizen Army, a volunteer armed force formed during labor troubles in 1913 to defend workers from the police. She would become

world famous for her role in the Easter Rising. Markievicz in uniform examining a Colt New Service Model 1909 revolver, posed c.1915

National Library of Ireland on The Commons

The 1916 Easter Rising is often compared to the American Revolution, illustrating what would have happened to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and the rest of the signers of the Declaration of Independance if the British had won the war. The Irish rebels 1916 Proclamation declared an independent Irish Republic and guaranteed ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and opportunities’ and would ‘pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole

nation." A little-known difference between the American declaration and the Proclamation is

that the Irish document was addressed to both men and women and guaranteed women's right to vote. It's estimated between 250-400 women participated in the Rising, with 77 being arrested and sent to prison. Some of the women who participated in the Rising pictured in Dublin in the summer of 1916. (Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum)

Constance Markievicz played a major role in the Rising, appointed second-in-command at a park in central Dublin, St. Stephen’s Green. She and her troops set up barricades and held them through the first day of the fighting, then retreated to defend their position at the Royal College of Surgeons for nearly a week before surrendering.

Countess Markievicz was the only woman court-martialed and sentenced to death along with the men leading the rebellion. At the court-martial on 4th May 1916, she plead not guilty to "taking part in an armed rebellion...for purpose of assisting the enemy" but guilty to attempting "to cause disaffection among the civil population of His Majesty," she said. "I went out to fight for Ireland's freedom and it does not matter what happens

to me. I did what I thought was right, and I stand by it". She was sentenced to death, but the court recommended mercy "solely and only on account of her sex." "Why don’t they let me die with my friends?” she asked.

Moved from Kilmainham Goal to prison in England, she was sentenced to hard labor and near-starvation rations. In failing health, she was released in an Easter Rising amnesty in 1917.

Destined to lives of comfort and privilege, in

1887, Constance and her sister Eva were presented at the court of Queen Victoria, but both sisters turned away from their aristocratic roots. Perhaps it was seeing the peasants on her father's estate during the 1879-1880 famine. They would have starved had he not provided food for them. Constance Gore-Booth with her sister Eva, also a suffrage activist. 1895

Constance did not look away from the deplorable plight of the poor in Ireland and jumped to action in 1913 when Dublin's

trade unions and mostly-British employers faced off, some 20-thousand workers going on strike or locked out of their jobs for five months. Crowded, disease-ridden slums in Dublin rivaled those in Calcutta, with a staggering death rate (27.6 per 1000) and even high numbers of infant mortality (147 per 1000). Unskilled workers competed for scarce jobs deflating wages. Constance helped set up a soup kitchen at the workers' headquarters during what came to be known as the Dublin Lock-out of 1913. She spent hours a day peeling potatoes, and that winter made regular trips to gather turf in the Dublin mountains, driving it to the city and

lugging bags of fuel up the dark stairs of crowded tenements to provide some heat for families of striking workers. It's little wonder five years later, the voters of a Dublin borough elected her to the House of Commons, making her the first woman member of Westminster Parliament in London. Though as a member of Sinn Féin she refused to take her seat. Irish revolutionaries refused to recognize the British parliament and instead established an independent legislature in Dublin, the Dáil ÉireannT. Constance was elected at the first meeting in 1919, and appointed Minister for Labour, the first female minister in a modern

democracy. However, she was back in jail, this time for working against the

conscription of Irish men to fight with the Bristish army in WWI. She would serve four more prison terms for her activist work in the following years. The bust of Constance Markiewicz in St Stephen's Green in Dublin.

Though Constance and her compatriots failed in the Easter Rising, the rebellion

sparked the Irish War of Independence resulting in the formation of the Irish Free State in 1921. Despite this new freedom from the British, women's rights almost immediately started to backslide. The new Irish government, influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, passed laws keeping women for sitting on juries, forced women working as teacher or civil servants to retire when they married, and limiting women's employment in general.

Laws in 1924 and 1927 largely excluded women from sitting on juries. Then in 1937, the new constitution sealed women's fate for decades, Article 41

stating “by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved. Today, woman in Ireland continue to push for equal rights and for remembrance and honor for the women, like Contance, who fought for a more just society. Countess Constance Markievicz died a pauper in the public ward of a Dublin hospital in 1927, suffering complications of appendicitis. Thousands of working-class people lined O'Connell Street and Parnell Square to pay their respects as her funeral procession passed by.

Like my article today? Please share:

Often, like today, I'm excited and eager to share a great story with you! The time I take researching and writing this newsletter, anywhere from 6 to 12 hours a week, feels like time well spent. But it takes a lot of coffee! If you'd like to buy me a cup, you can

do that.

Thank you! I've been sending my newsletter for nearly ten years for free. And I promise you, I will never charge you a fee to read

it. You support me in so many ways! Sharing your interest in the

women I write about, telling me when a story inspires you, thanking me for a timely and important article, sharing book recommendations.... You encourage and support me when I'm struggling, when I feel alone and when I need help. You buy my books and recommend them to friends and family. There's no way I could put a price on this. But if you are so inclined, you can buy me a cup

of coffee. Not a fancy Starbucks. I make mine at home every morning. No pressure. It's not required. Only if you feel like it. Thank you for all the ways you support me and my writing. I don't take you for granted.

Follow me on social media

Read a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link

below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this

newsletter. |

|

|