August 25, 2023 Hello , A significant anniversary date, August 20th, slipped by me earlier this week, but it's never too late to tell an important story about a woman worth remembering. That day in 2001, the U.S. Army finally honored the service and courage of the chief nurse who commanded the American nurses taken POW by the Japanese in WWII. Major Maude Campbell Davison received the Distinguished Service Medal. Unfortunately, the award and the recognition came late, fifty-six years after the war's end and forty-six years after her death.

ANC Major Maude Davison after her release from captivity, 1945

The dozens of army nurses held in captivity for three long years in the Philippines may not always have liked Chief Davison, but she was determined to do everything

in her power to assure they survived.

She was a "Prescription for Endurance and Courage"

Captain Maud Davison had only recently taken command of the Army Nurse Corps in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked in December 1941. A deluge of wounded immediately swamped every U.S. army and navy medical facility on the Island of Luzon. Explosions rocked Sternberg Army Hospital in Manila, the largest, most well-equipped US medical facility in Southeast Asia. Light fixtures swung, windows shattered, glass sprayed, patients screamed. The concussion from a bomb knocked Capt. Davison to the floor, injuring her spine an making her a patient in her own

hospital.

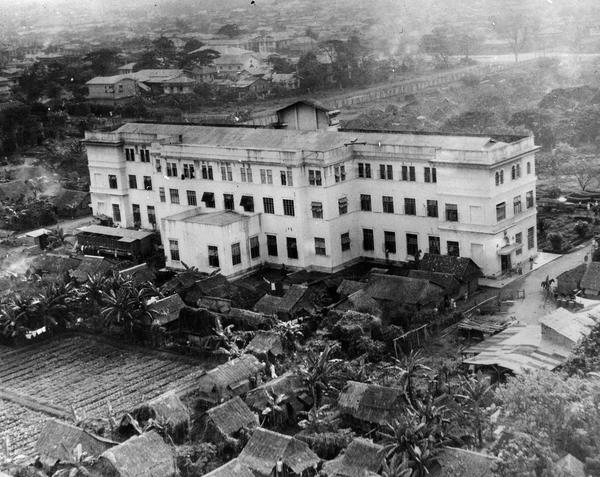

Sternberg Hospital, Manila, Philippines before the Japanese attack. (Photo courtesy Army Nurse Ethel Thor)

Capt. Davison did not stay down for long, by Christmas she had evacuated all the nurses under her command to safety at American strongholds on Corregidor and

Bataan. The Japanese Army had invaded Northern Luzon, marching toward Manila. American forces gathered to cut off their advance. Nurses prepared for battle, organizing

a field hospital in the Bataan jungle.

U.S. Army Nurses Josie Nesbit, Chief Maude Davison and Helen Hennesey. During a lull in the fighting, Davison

arrived from Headquarters at Fort Mills hospital on Corregidor to inspect two field hospitals on Bataan. Unfortunately, she had to cut her visit short. Walking the 17 wards of hospital #2, (25 difficult miles) exhausted the 57-year-old chief nurse and aggravated her earlier back injury.

When WWII

broke out, Canadian-born Maude already had two careers and as many diplomas under her belt. She worked as a dietitian Brandon, Manitoba before immigrating to the U.S. in 1909, where she served as a dietitian and instructor in domestic science at Epworth Hospital in South Bend, Indiana. She returned to Canada for several years, graduating in 1917 from the Pasadena Hospital Training School for Nurses with her R.N. degree. By that time the U.S. had entered WWI and Maude joined the U.S. ANC Reserves as a staff nurse Camp Fremont hospital in Palo Alto, California. Later while serving in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, she became an American citizen and transferred to the

Regular Army of the Nurse Corps Her expertise in nursing and dietetics made her a valuable officer at a time when the army was assigned the difficult jobs of

coordinating casualties of the Great War, helping with refugees abroad and a flu epidemic at home. In the early 1920 she spent 13 months with the occupation forces and Coblenz, Germany aiding victims of the famine then sweeping Russia and Eastern Europe. Maude earned her Bachelors in home economics at Colombia in 1928, when less than 10% of women in the United States held college degrees. She then returned to the ANC serving throughout the US and moving up in the ranks until in 1939, when she was deployed to the Philippines, promoted to captain and chief nurse in 1941. That Decemeber, U.S. and Philippine armies retreated to the Bataan Peninsula as the larger, more well-armed Japanese army took control of almost the entire Island of Luzon, including the city of Manila. Three months of intense fighting

later, Americans surrendered Bataan, Army nurses barely escaping across the water to underground tunnels on the "Rock," as Corregidor Island was known.

U.S. Army Nurses and doctor treat wounded soldiers, Fort Mills Hospital, Corregidor,

Philippines, 1942. (US Army Photo) Burrowed underground on the last bastion of Americans, nurses lost track of day and night as double-stacked beds and tripled them as the battle raged above. Bombs pounded the Rock, shaking

the walls and ceiling, medicine bottles toppled, bunk beds scooted. Under direction from Captain Davison, nurses remained calm and proficient. After months of combat nursing, they suffered exhaustion and tropical diseases like dysentery, malaria and break-bone fever. The Japanese attacks intensified, medical supplies and food dwindled. But the worst was yet to come. American forces

surrendered. The women were captured. The first group of U.S. Army women sent into combat, then became the first ever surrendered to an enemy. Captain Davison did her best to protect them, making it clear to the Japanese that the women were officers of the United States Army, and should be treated as such. She ordered the nurse to dress in their khaki uniforms at all times, with their Red Cross armbands on their sleeve in the hope the Japanese would respect the international symbol for noncombatants. Six weeks after the surrender of Corregidor, the nurses were forcibly separated from their patients and sent to Santo Tomas Internment

Camp in Manila, where the Japanese imprisoned allied civilians.

Main buildings and shanties built by prisoners at Santo Tomas Internment Camp, Manila, Philippines, National Archives photo.

At the prison camp army nurses were

assigned to clean toilets. Capt. Davison went right to the Japanese Commandant and demanded her women be sent to nurse captive American soldiers. Though a small woman

with her white hair in a bun, Capt. Davison had a backbone of steel and did not back down. If they had to stay in a civilian camp, she insisted the army women work in their professional role. The Japanese agreed they could set up a hospital in the camp and continue as nurses. Some of the younger army nurses balked at Capt. Davison's domineering style and at taking care of civilians. They challenged Captain Davison's authority over them in a civilian camp, but her iron will prevailed. She demanded the nurse follow army regulations and her rules to the letter, upholding the highest standards of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps. She pulled her nurses together as a unit, insisted on discipline, order and dedication to their patients. Elizabeth Norman, who interviewed many of the nurses for her book We Band of Angels wrote: "[Davison's] discipline for discipline's sake rather a prescription for endurance and courage. Stick to the job, she told them, and they might just make it home. She may not have been genial or empathetic, but she was a leader, the captain who [kept her nurses alive." The army nurses barely survived their three years in prison camp. When US forces liberated Santo Tomas February 3, 1945, all were weak from near-starvation and disease. A number were patients in their own hospital.

Sixty-year-old Maude Davison was in the worst shape suffering from an intestinal obstruction and starvation. She weighed only 80 pounds.

Army nurses recently liberated from captivity in the Philippines touch down at Hickam Field in Hawaii on their

way home. Captain Maude Davison front row, third from the left.

After three years as a POW, Major Maude Davidson wanted to return to active duty, but at age sixty and in poor health, the army retired her in January

1946. Army doctors who served with Maude Davison nominated her for the army's third highest decoration, a Distinguished Service Medal, for her leadership, valor and

sacrifice on Bataan and Corregidor and throughout the nurses' captivity. Colonel Wibb Cooper, wrote to the U.S. Army Awards and Decorations Board: "It is my feeling that no group of American nurses have ever been subjected to a more difficult or hazardous situation than during the Philippine campaign, and the influence of major Davison's leadership was a large contributing factor toward the outstanding dignified courageous performance of this small group of nurses.... As chief nurse... responsible for all nursing activities... she displayed exceptional leadership and judgment... and by her cheerful and energetic

matter of carrying on her duties under the most unusual and trying conditions she was inspirational only to the members of her own corps but to all others with whom she came in contact. Unfortunately, army brass decided the appropriate medal for Major Davison was The Legion of Merit, a commendation for a job well done. The award was appealed to the Secretary of War, to which a member of the Awards and Decorations Board replied that it did not appear Major Davison met the criteria for the Distinguished Service Medal: "In determining the degree of responsibility in [Davison's] case it is apparent that a large share must have been carried out by doctors and commanders...."~September 9,1946. Thanks to the efforts of supporters, including surviving POW nurses, Brigadier General [Ret.] Connie Slewitzke, Senator Daniel Inouye, and Elizabeth Norman, the situation was rectified. August 20, 2001, Commander Maude Davison was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service medal.

Like my article today? Please share:

Follow me on social media

Read a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this

e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help

students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this

newsletter. |

|

|