May 10, 2024 Hello , The people of Appalachia get kicked around in the national consciousness with words and images like hillbilly, poverty, coal miners, banjos, opioid addiction, diabetes, heart disease, Trump supporters, and Confederate flags. We can find someone to fit every stereotype we come up with. Or we can delve into the stories of individual people like the Widow

Combs of Knott County, Kentucky. In November 1965, she made history, one of a number of Appalachian women caught in the headlights of the industrial machine who rose up to demand justice. When the Caperton Coal Company came for Ollie Comb's farm, ready to rip up everything from the ground's surface to get at the coal underneath, the

61-year-old woman sat down in front of the bulldozers and refused to get out of the way.

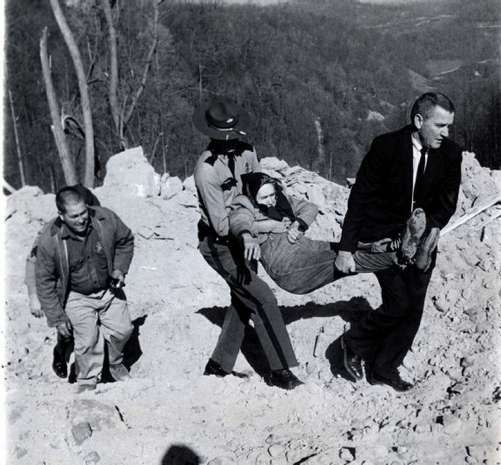

Unfortunately, I can't show you any photos of Ollie seated on her land in hopes of saving her home. The Louisville Courier-Journal news photographer on the scene, Bill Strode was relieved of his camera by police. Strode did take some photos at a later date.

Ollie Combs standing next to bulldozer in protest of strip mining on her

land. Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016, Hamilton College (Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art) “I didn’t want to them to come through," she explained. "I didn’t want to see my home ruined. It’s all I’ve got

left.” Caperton Coal Company management argued with Ollie. Dozer operators pleaded and wheedled. She refused to give in.

Gift of Thomas J. Wilson and Jill M. Garling, P2016, Hamilton College (Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art) Appalachia is not the poor white monoculture often portrayed in popular media. There's bound to be a lot of diversity among 25 million people spread over 700,000 square miles, including regions in five to 13 different states depending on the definition you choose. The Combs family was rooted deeply in Appalachia, pioneers in the family arriving in Kentucky in 1795. Prior to WWII, most white people were coal miners or farmers, raising crops and livestock on rugged land with deep gorges, high ridges and thick forests. In the first half of the 20th century many women kept

house without electricity. Babies were born at home. "It was tough, but it was often beautiful. The air was clean, the woods filled

with life, and the stars shone beautifully at night. It’s the Appalachia most of us instinctively long for," Dr. Mollie Cecil, a young West Virginia native with a medical degree and a master's in history. After World War II, the coal industry changed methods, moving from digging coal underground to strip mining. Rather than tunnelling into hills, they blasted away hilltops and scoured away everything on the ground surface to get at the coal.

Homes, barns, and graveyards were all leveled," says Mollie Cecil. "[People] watched as their family cemeteries, dating back generations, were ruined. One woman watched as the coffin of a child that died in infancy was ripped from the ground and sent tumbling over the hillside." This was possible because of a legal document called a broad form deed, by which farmers sold mineral rights but retained their surface land. The deeds were common roughly 1785-1915, when coal was commonly extracted by tunneling underground and leaving the surface untouched. In Knott County, KY, coal companies owned broad form deeds to about ninety percent of the land and by the 1960s, they were ravenous, leaving no stone unturned. The supreme court

upheld their right to get the coal no matter how much the land was damaged. When Ollie Combs and her two sons refused to allow Caperton Coal bulldozer onto her land,

the company asked a local judge for a restraining order. “I just want to live out my life in my hollow and be left

alone,” Ollie said. Two days later, she and her sons were arrested. Initially, she went along with police, but as they went down the mountain, she

became less abiding.

Ollie Combs being removed from the protest site. Photo credit: Lexington Leader-Herald. Photograph by Bill Strode, who was also arrested. “I was just tryin’ to see how heavy I could be”, she later remembered. “I wanted to see what they would do. I didn’t think they would actually carry me off.” The judge sentenced the widow and her boys to 20 hours in jail, beginning on Wednesday, November 24th. The next day was Thanksgiving, and he had no mercy.

Ollie Combs and her sons eating Thanksgiving dinner in jail. (Lexington

Leader-Herald.)

Shamed by the bad press following Ollie's arrest, Caperton Coal never bulldozed her land extracting the coal through traditional tunnelling. Her act of resistance hit the news across the nation, and she

became an inspiration to other landowners in Appalachia who followed her example to protect their homes. Even more important, her action and story sparked change. She spoke as a witness at hearings about strip mining which led to legislation in Kentucky that mandated stricter surface mining guidelines, and eventually the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of Congress. Though, that law wasn't passed until

1977. The broad form deed proved a tough nut to crack. People organized, protested and lobbied for two decades before Kentucky courts reinterpreted landowners' rights to their surface property. After ten years fighting the coal companies, protesting and working for change, Ollie returned to her private life and caring for her disabled

son. In 1976 at age 71, Ollie agreed to allow the coal company access to mine the hill above her home, negotiating for protection of her house, financial compensation, a telephone line and an orchard as part of the mine reclamation. The company also flew her disabled son to a specialty hospital for evaluation and treatment. "After years of hard living, who could blame her for agreeing to these concessions" says Mollie Cecil. "It was a very pragmatic decision, although not popular amongst many people who had continued to fight against strip mining." Ollie Combs joins a bevy of historical Appalachian women to take a stand for justice against the powerful resource extraction corporations.

Kentucky women occupied equipment at a Knott County strip mine site in protest, January

1972. Photo courtesy Anne Lewis, Documentary Film Maker TO SAVE THE LAND AND PEOPLE

The Appalachian group To Save the Land and People tried to protect their land

from strip mining in the early 1970'a with a variety of tactics from lawsuits to guns and dynamite. The abundant natural gifts of Appalachia can be a "resource curse"

for people of the region. Outside interests have reaped the profits from the clear-cutting of hardwood forests in the early 20th century to the massive extraction of coal to this day. Mountain people have gained little from these riches and yet the promise of jobs is enticing. It's no easy paradox to live with. The beauty and bounty of the natural landscape also inspires pride, independence and community traditions of resistance.

“Women putting their bodies on the line—because that is really what they’re doing— has been a historical pattern,” said Jessie Wilkerson, author of To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social

Justice. “They always center what I and other scholars call ‘caring labor.’ They’re really emphasizing the labor that it takes to sustain life, to take care of other people, to take care of children, to take care of the environment, to take care of their communities.”

In Appalachia today, Ollie Combs' spirit of resistance is alive as the fight continues to protect not only private land, but drinking water, clean air, and the environment.

Like my article today? Please share:

Sources https://annelewis.org/to-save-the-land-and-people/

A few years ago, the book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J. D. Vance was all the rage and was then made into a movie. In the memoir, Vance strongly suggests his family was responsible for its own misfortune and

blames hillbilly culture and a supposed encouragement of social rot for poverty, drug and alcohol abuse and poor work ethics and believing economic insecurity plays a much lesser role. Now there's, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia by Elizabeth Catte, a frank assessment of America’s recent fascination with the people and problems of the

region. Review from Cinda on Goodreads Anyone who has read Hillbilly Elegy owes it to him/herself to follow up with this book. Better yet, skip Elegy and read this. As far as I can tell, Vance

never actually lived in Appalachia. Not only was Catte born and raised in Tennessee, but she is steeped in the economic history of the region. She has strong opinions as well as the academic chops to back them up. Unlike Vance, she achieved success while maintaining an abiding respect and regard for the people she grew up with.

On publishers

website: "This is a necessary antidote to the cyclical mainstream interest in Appalachia as a backwards, white working-class caricature.”

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|