May 17, 2024 Hello , History happens in the eyes of the beholder. No story illustrates this quite like that of the Queen of Jhansi who went to war holding her reins in her teeth, two swords in hand and her child on her back. This image comes from an all-is-lost moment in 1857, when the British Army stormed Jhansi and the Hindi queen

fled into the night to fight again another day. Fighting had broken out in the garrison town of Meerut led by thousands of Sepoys, Indian soldiers hired into the British Army. The British declared it a mutiny. But the fighting quickly spread to other army posts and was joined by

civilians and Indians called it the Great Rebellion. Two-hundred-and-fifty years later, we know it as the First Indian War of Independence, and the Queen or Rani of

Jhansi has emerged as a symbol of India's courage and perseverance in the initial struggle for freedom. But not before British historians took a crack at spoiling her

reputation.

Brave Warrior or Wanton Woman?

Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi, named Manikarna "mistress of jewels" at birth, was uniquely qualified to lead her people in peace and in war. Her mother died when the girl was four years old and she was raised by her father, an advisor in the court of Peshwa of Bithoor. Unlike most girls at the time, Manikarna learned to read and write beside the boys at court and trained in fencing, shooting, martial arts, horseback riding and the ancient gymnastic form of mallakhamba.

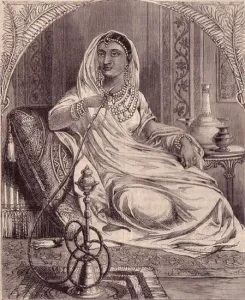

Miniature of Rani of Jhansi found during the capture of the

Nawab of Farrukhabad's palace in 1857, National Army Museum, Public Domain.

At the time of Manikarna's lifetime, India was an expanse of many small princely states falling under the rule of the British East India Company acting

as a sovereign power for the British Crown. At fourteen, she married Maharaja Gangadar Rao ruler of the Kingdom of Jhansi who was twenty years older than she. As was custom

for a queen, she chose a new name and became known as Rani Lakshmibai. Shown below her royal chambers, Lakshmibai appears a traditional young royal woman of the time. She was anything but.

Lakshmibai

didn't adhere to the Hindi purdah norms under which women concealed their skin and figures with veils or curtains and were kept separate from men. Perhaps because she got a taste of freedom growing up with boys in the court of Peshwa. She found wearing a turban like a man more practical, especially when exercising to keep up her physical prowess, as well as practicing with weapons at the palace. She trained other women as well, forming a regiment of women soldiers.

“This may not have been quite so unusual as it appears,” writes Allen Copsey, who has extensively researched the rani’s life. The palace women’s quarters were often guarded by armed women, and these women warriors did sometimes fight in battles. “What was unusual was for the rani to be in charge of their training.”

In 1851, the young rani gave birth to an heir, but the baby did not survive. Two years later, the maharaja lay on his deathbed. Realizing he would die without an heir, he and his wife Lakshmibai quickly adopted a boy baby, whom they hoped the British would recognize as the rightful maharaja or king. Lakshmibai was to rule until the boy came of age. Lakshmibai refused to behave in the expected way for childless Hindu widow such as shaving her head, breaking her bangles, and submitting to restrictions on what she could wear, eat, her psychical movement and social activities. She appealed face to face with British officials, pleading to retain the right to rule Jhansi. Despite the fact the independent princely state had supported a pro-British stance prior to the king's death, the British East India

Company seized the territory and refused to recognize the rule of rani or her adopted son. Apparently, that's when she uttered her famous cry. “Mera Jhansi nahin dengee!”–Hindi for “I will not give up my Jhansi!” Which is easy to picture when you see her portrayal in a recent

biopic.

Biopic, Manikarnika, 2019, courtesy Instagram.

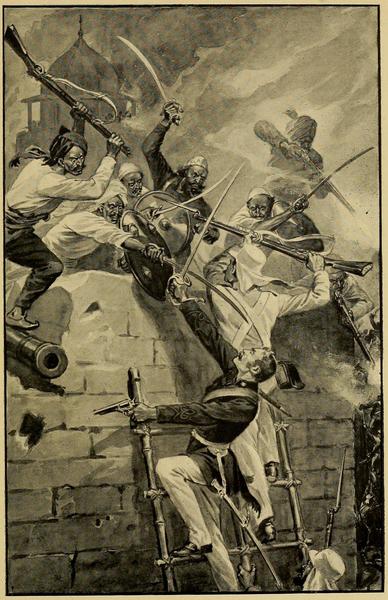

Rani Lakshmibai tried to negotiate with the British to send soldiers to protect Jhansi after the eruption of violence in 1857. They refused and by the following year she had raised an army of 14,000 volunteers and secured the loyalty of an additional 15,000 Indian troops serving in the British army. She directed a foundry which cast cannon for long range defense. The British attacked Jhansi

March 28, 1858, and the warrior queen led her army into battle defending the city against British siege for five days. Then under heavy cannon fire, four columns of British approached to scale the city walls.

The fight for Jhansi. Wikimedia Two British columns entered the city from another direction. The rebels found hand to

hand and street to street, but the British made progress toward the palace. That is when, according to tradition, the warrior queen jumped on her horse Baadal with her son on her back and escaped into the night to fight another day.

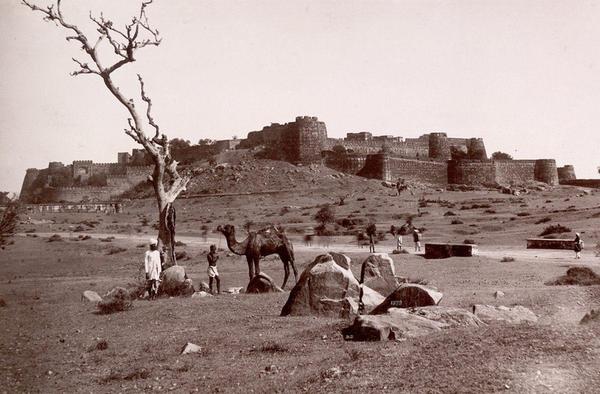

Rani Lakshmibai's statue in Solapur near the Kambar Talav | Wikimedia Commons Several months later, Rani Lakshmibai faced the British again at Gwalior where the fort held by rebels fell on June 16, 1858. Still commanding a large Indian armed force the next day,

the warrior queen died in the midst of battle.

The fortress at Jhansi in about 1882. The British stormed the fort in its attack on the town in

1858.

The people of Jhansi loved and respected their queen, they knew her to be compassionate and of the highest character. In battle, they witnessed her bravery, fortitude and heart.

In the eyes of the British, she was something else. John Lang, the first white person to see her, wrote this description. “She was a woman of about middle size—rather stout but not too stout. Her face must have been very handsome when she was younger, and even now it had many charms— though

according to my idea of beauty, it was too round. The expression was also very good, and very intelligent. The eyes were particularly fine, and the nose very delicately shaped. She was not very fair, though she was far from black. She had no ornaments, strange to say, upon her person, except for a pair of gold ear-rings. Her dress was a plain white muslin, so fine in texture, and drawn about her in such a way, and so tightly, that the outline of her figure was plainly discernible—and a

remarkably fine figure she had.” Lieutenant George Forrest (who sacrificed his life for the British cause) called Rani Lakshmibai an "ardent, daring, licentious woman.". One Englishman, Colonel G. B. Malleson wrote in his History of the Indian Mutiny, “Whatever her faults in British eyes may have been, her countrymen will ever remember that she was driven by ill-treatment into rebellion, and that she lived and died for her country.”

Portrait of Lakshmibai, the Ranee of Jhansi, (1861 by Royal Artist of Jhansi Ratan Kushwah in Indore)

Probably done after her death (June 1858): she wears a valuable pearl necklace and a cavalrywoman's uniform Public Domain But the stigma and slander of British

historians could not last. Over the following decades, Lakshmibai emerged as a symbol not just of resistance but of the complexities that come with being a powerful woman in India.

“Her story has come to us less as history and more as mythology,” Harleen Singh, an associate

professor of literature and women’s studies at Brandeis University, said in a phone interview. “It’s female heroism that is bound to the family and the nation.”

In the 1940's, the Indian National Army formed an all-female unit that helped in the fight for independence, which did not come until 1947, 90 years after Lakshmibai's death.

Today,

Rani Lakshmibai is remembered, honored and celebrated in movies, TV shows, books and even nursery rhymes. Streets are named for her and statues portraying her famous escape with her son on her back rise in cities across India. Maybe most significant, little girls love to dress up like her, wear pants, turbans and wielding swords.

Like my article today? Please share:

Sources https://ozwisdomsandlessons.com/rani-of-jhansi-revolt-of-1857-heroine/

Thanks to subscriber Norm Haskett, (Daily Chronicles of WWII) for alerting me to a new World War II-era film, Lee, based on the life of famed war correspondent Elizabeth “Lee” Miller. Kate Winslet directs and stars in the movie, an adaptation of the book detailing Elizabeth Miller's wartime exploits, The Lives of Lee Miller. It co-stars Andy Samberg and Andrea Riseborough.

I love this quote from Kate Winslet: “Lee was a woman who lived her life on her terms. I wanted to tell the story of a flawed middle-aged woman who went to war and documented it.” The movie is expected to debut in American theaters September 20, 2024.

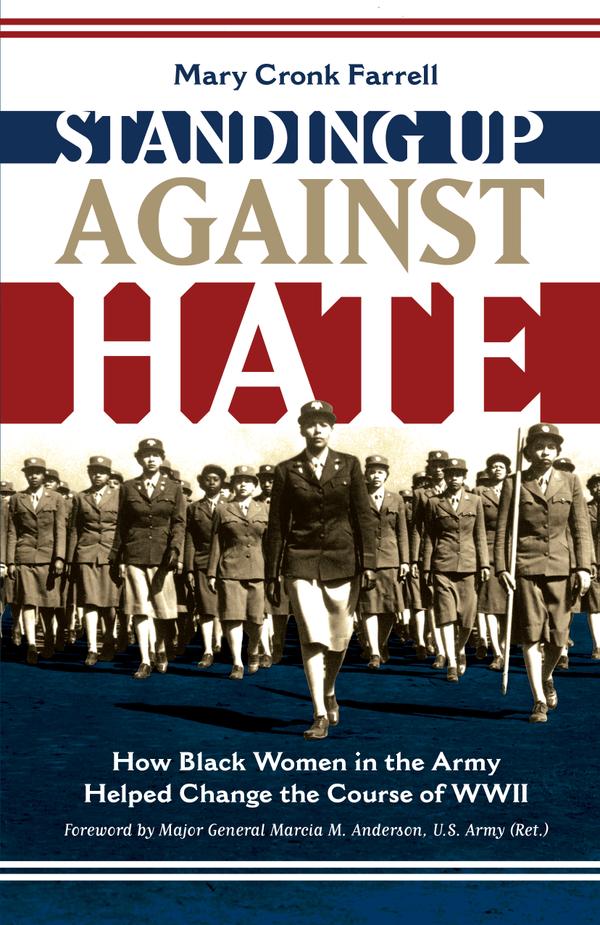

In other news, the opening of a new exhibit honoring the now famous all female, all Black #6888th Postal Directory Battalion, under the WWII command of Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the first Black woman

commissioned as an officer in Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. Fittingly, the exhibit Courage to Deliver is located at the Army Women’s Museum at Fort Gregg-Adams, previously

known as Fort Lee after the Confererate General. Last year the army post was redesignated to honor Lt. Col. Adams and retired Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg. Gregg is the Army’s first Black three-star general, Stanley Earley III, the son of the late Charity Adams-Earley broke down in understandable terms the accomplishment of the 6888th in redirecting a baglog of letters and packages to American soldiers fighting in

Europe. “There’s 60 seconds in a minute and there’s 60 minutes in an hour, and these women worked eight-hour shifts which would give you a total of 28,800 seconds," he said. "These women were sorting 65,000 pieces of mail every shift, which means they were processing a piece of mail every .44 seconds.”

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|