May 31, 2024 Hello , The name that comes to mind at mention of the WWII Battle for Manila is General Douglas MacArthur, famous for liberating the Philippines from three-years of brutal Japanese occupation. Less well-known is the woman known as the brains behind the guerrilla army that led the charge to secure water for a city dying, not only from bombs and gunfire, but from thirst. How did a woman from Denver, Colorado, mother of three and radio news reporter become Colonel Yay of the ruthless Marking Guerrilla Army based in the Philippine jungle? That's the question answered in today's story. But first a question for you. I need a few beta readers, readers willing to give feedback on a manuscript. You

don't have to be a writer, only an avid reader who's willing to give construction criticism. Hit reply to this email and tell me if you're interested. I'll send you more information.

The Brains Behind the Brawn!

In the late 1930s, Yay Panlilio was possibly the most well-known woman in the Philippine Islands. A mestiza, raised by an Irish American father a Filipina mother in Denver, Yay left Colorado as a teenager to become

a journalist in the Philippines. Yay had married at sixteen and had three children, becoming a working, single mother when the relationship ended. She was passionate about journalism and her work as a reporter for The Philippines Herald and news broadcaster for KZRH radio was recognized by both Filipinos and Americans.

Pre-War photo of Yay Panlilio. Yay was at work on a story in Baguio, in the mountains north of Manila on December 8, 1941, when a small US Army post there was bombed by the Japanese in their initial surprise attack on the

Philippines. Continuing as a journalist, she passed intelligence to U.S. forces. When the Japanese took control of Manila, they kept Yay

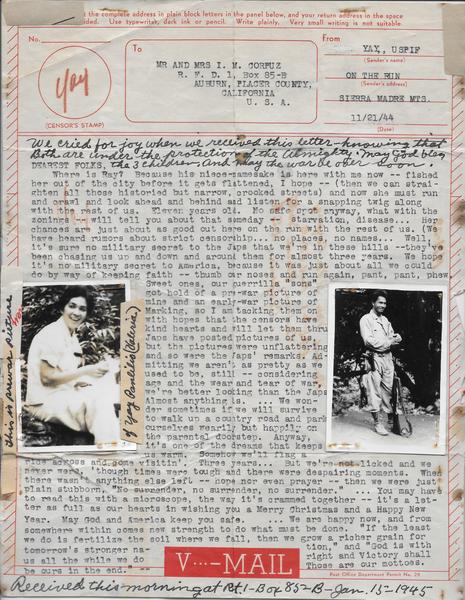

on the radio to broadcast propaganda. For a while, she was able to include coded messages to resistance fighters amassing in the jungle. When the Japanese caught on, she fled before they could arrest her. Leaving her three children in the care of friends, she joined the underground resistance in the jungle. Writing a letter to her mother in America, Yay gave the return address: on the run in the Sierra Madre Mountains and described the life "[We] run and crawl and look ahead and behind and listen for a snapping twig along...no safe place...starvation, disease..."

Letter home dated 11/21/44. Yay included a photo of herself and Guerrilla

Leader Marcos Villa Augustin. Among the resistance fighters, one stood out to Yay, Marcos Villa Augustin, known as Marking, was a former cab driver and boxer from Manila. They were opposites, he brusque and uncouth; she calculating and sophisticated. When they fell in love their relationship was tempestuous, but they worked well together, and she became second in command of the Marking

Guerrillas. An initial group of 150, partially armed and untrained men and women playing cat and mouse with Japanese patrols, grew, over the next three years under Marking's aggressive leadership to an army of more than 10,000, possibly 20,000 by the end of the war. Yay was recognized as the brains of the outfit and a US army report

called her the backbone of the organization. She was responsible the groups communications, policies and funds smuggled to her by the US military. Yay had a price on head and sometimes wondered if she would survive, but there was no thought of quitting. She wrote her mother in 1944. "[It's been] three years… but we're not licked and we never were, though times were tough and there were despairing moments when there wasn't anything else left-- hope nor even prayer-- then we were

just plain stubborn. No surrender. No surrender. No surrender."

A large formation of guerrillas march under the U.S. flag. Photo Courtesy University of Wisconsin Many resistance fighters and their families lost their lives opposing the Japanese. Yay was willing to give hers, saying, “Filipinos will die for love, and Americans will die for principle. I am half-and-half. I die the same way.” Back when I was in school, we learned mostly about WWII in Europe. The war in the Pacific was shortened to the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima. I sometimes wonder if the teachers ran out of time or steam at the end of the semester, or if the Japanese conquest

of the brown people in Southeast Asia didn't seem as important. At any rate, the suffering of the Filipino people under Japanese occupation was a huge revelation when I researched my book about American POW nurses in the Philippines. Three years of brutality on the Island of Luzon culminated in the battle of Manila. Military

historians rank it one of the most savage and destructive urban battles ever fought and the largest ever waged by American forces. Manila stands with Berlin and Warsaw as the most devasted capital cities of WWII.

A stretcher party brings out a wounded U.S. soldier after an attack by U.S. troops on Feb. 23, 1945, to liberate Filipino prisoners in Intramuros, Philippines. (Naval History and Heritage

Command)

During the February 1945, month-long battle, 1,010 U.S. soldiers died and 5,565 were wounded. An estimated 100,000 Filipinos civilians were killed, either deliberately massacred by the Japanese or struct down by U.S. or

Japanese artillery fire and bombs. It's unknown how many Japanese soldiers died, though 16,665 were counted within the last bastion of the walled city. General MacArthur declared to Filipinos, "Your capital city, cruelly punished though it be, has regained its rightful place—citadel of democracy in the East." The citizens of Manila were free, but if MacArthur didn't do something quickly, they'd die of thirst and disease. The half of the city located south of the Pasig River had no drinkable water except that trucked in by the US Army. Water pressure was too low to flush sewage, clogging

toilets and backing up refuse throughout the city. Restaurants and night clubs filled with off-duty American troops could not keep up minimum sanitary standards. Military units and civilian people streamed into the city adding to the shortage of water. It was prime breeding ground for a number of epidemics.

The Battle of Manila left thousands of civilians dead or wounded. Here, Filipino survivors gather after

their liberation by U.S. troops on Feb. 23, 1945. (Naval History and Heritage Command) One major source of water for Manila was the Ipo Dam straddling the Angat River in the Sierra Madre mountains. That's where Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita had entrenched his army. MacArthur knew he must

seize the reservoir before the Japanese could blow the dam, but he was directing an ambitious agenda waging battle in three other regions of the island. The most direct route to Ipo was a two-lane road through steep limestone bluffs honeycombed with caves sheltering Japanese soldiers. To leave the road, American soldiers would have to traverse over jumbles of rock and brush outcroppings, ideal hiding spots and

camouflage for the Japanese. “Morale was down, men and officers alike were tired and worn, and all units were sadly understrength, especially in combat effectives," according to Army historian Robert Ross Smith. "The 6th Division had suffered

approximately 1,335 combat casualties—335 killed and 1,000 wounded—and over three times that number of men had been evacuated from the front lines either permanently or temporarily for non-combat injuries, sickness, and psychoneurotic causes.”

Water rushes through a spillway at Ipo Dam. Capturing the reservoir intact meant that enough water would be available to supply American troops and Filipino civilians in Manila. The Yay Regiment had been harassing small groups of Japanese soldiers in the area and transmitting information to MacArthur’s headquarters for the last three years and were known to be trustworthy and familiar with the territory. Yay herself had gone to Santo Tomas Interment Camp in Manila to check on her children. But her guerrilla force joined the

mission to Ipo Dam. It was mid-May when the goal came in sight, but torrents of rain drenched the region halting U.S. Army operations. The terrain was impassable. Trucks carrying ammunition, rations and medical supplies were mired in mud, artillery, tanks and mortars

immobilized. On foot, a Yay Regiment patrol pressed on, fighting hand-to-hand, making its way down the opposite side of the Angat. Wading across the river, the guerrilla

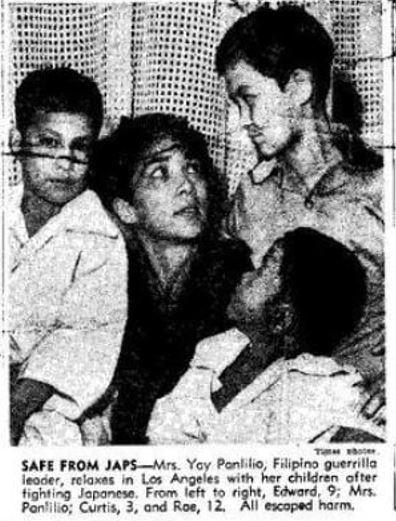

raised the American flag over the powerhouse on the south bank capturing Ipo Dam. According to U.S. Army historian Robert Ross Smith, the Yay Regiment, which suffered 40 dead, deserved "the lion's share of the credit for the capture of the Ipo Dam." Yay's children survived the war, though she said they had witnessed the cruelty of the Japanese. Nearly all the prisoners at Santo Tomas suffered starvation and disease. The family sailed to the U.S. that spring, arriving in Los Angeles, where she was interview by the local paper.

Los Angeles, August 1945.

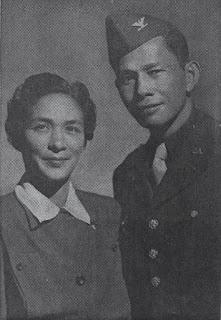

In September 1945, Yay reunited with General Marcos Villa Agustin and they married in Chihuahua, Mexico, though they later divorced.

Yay and Marcos Villa Agustin. Yay Panlilio's memoir The Crucible, was published in 1950 and she was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom. Unfortunately, in her written works, Yay downplays her experience and accomplishment as “an outspoken journalist, guerrillera spy, and Filipino patriot”, emphasizing the contributions of men, like her husband. Which makes it all the more important that we remember her story, her courage and her commitment to her people.

Like my article today? Please share:

Sources https://womenheroesofwwiipacific.blogspot.com/2016/06/blog-post.html https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Yay_Panlilio

"This is part helpful informational text and part enthralling narrative; each of these 15 profiles could constitute a cliff-hanger screenplay." --Booklist, starred review

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|