June 14, 2024 Hello , Some say Lydia Darragh was America's first woman spy. Listening through a keyhole she learned the British planned to attack the Continental Army and walked sixteen miles in deep snow, uphill both ways to get the message to George Washington. It's difficult to know the truth about history. Part of the fascination is analyzing

what information can be found and debating its interpretation. I have my own theory about Lydia, who cast aside her Quaker pacifist beliefs and took deliberate action during the American Revolutionary War. There are two main sources for this story, an account

published by Lydia's daughter Ann and the journal of Elias Boudinot, Commissary General of Prisoners in the Army of America. A lot can be inferred from these documents and the details added by well-meaning storytellers through the years.

Lydia Darragh, Revolutionary War Spy

The War for Independance had continued for two and a half years when in September of 1777 the British and Continental armies met at Brandywine Creek. This became the largest battle of the war in terms of the number

of fighting soldiers and the longest single-day conflict lasting eleven hours.

Battle of Brandywine, Howard Pyle (Public Domain)

The British won the battle, forcing George Washington's troops to retreat and two weeks later the redcoats marched triumphantly into Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress. The American Army retreated to Whitemarsh, sixteen miles away and Congress fled Philadelphia, as did nearly one-third of the population, leaving mostly British sympathizers and Quaker pacifists in the

city. William and Lydia Darragh were among the Quakers who remained but sent their two youngest children to stay with relatives in the country for safety. The Irish couple had married in Dublin in 1753 and immigrated shortly after to America. According to Dorothy Stanaitis, a Philadelphia tour guide, Lydia was a midwife and mother of nine children, though only five survived infancy. To all observations, the Darragh's remained pacifists, though their oldest son Charles had joined the War for Independance, serving with 2nd Pennsylvania regiment. He was camped at Whitemarsh.

Lydia Barrington Darragh. Library of

Congress

Lydia first showed her metal when the British tried to commandeer her house. British General William Howe had taken over the nearby Cadwalader house and his officers wanted hers. With no place for her family to go, Lydia determined to meet with the general himself and plead to keep her home. She was stopped by a British officer, Captain

Barrington, who turned out to be shirttail relation from Ireland. He spoke to Howe on her behalf and gained permission to stay in her home if she provided a room for British officers to hold meetings. One source indicates Lydia immediately started spying on the British, coming into their meetings with food and drink or more wood for the fire. She hid written notes under the cloth of buttons on her son John's coat. Josh then delivered

the messages to his brother Charles encamped with General Washington.

Lydia Darragh house, Little Dock Creek and 2nd Street, roughly 80 years after she lived there. Library

of Congress, Frederick De Bourg Richards, photographer.

On

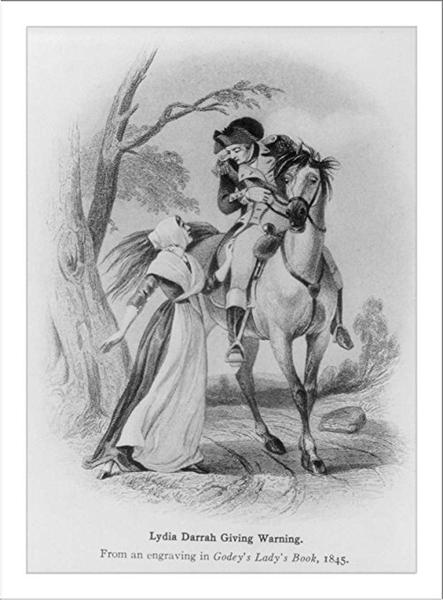

the evening of December 2, 1777, the British arranged to hold a meeting at the Darragh house, asking the family to retreat to their bedrooms for the duration. Lydia hid in an adjoining closet, or she listened at the keyhole, and what she heard turned out to be very important. General Howe and his officers planned to attack American forces at Whitemarsh in two days' time. Perhaps Lydia knew at once what she must do, or maybe she lay awake during the night figuring out her best plan of action. But early the next morning, she inquired for a pass to leave the city to buy flour at a gristmill some miles away in Frankford. Lydia walked north along the snowy road, crossing the British lines with an empty flour sack. According to the account published 50 years later by her daughter Ann, Lydia ran into a friend on the road,

Colonel Thomas Craig and asked him to pass along a warning about the impending attack, then returned home with her sack of flour.

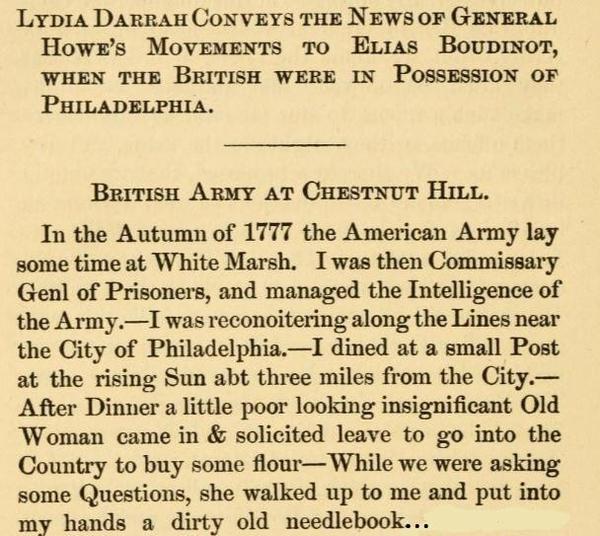

A needlebook is a handy little organizer with pockets to store all your needles in one place, still used today by seamstresses and crafters. "On opening the needlebook," wrote Elias Boudinot, "I could not find anything till I got to the last pocket, where I found a piece of paper rolled up into the form of a pipe shank [A pipe shank is the part of a tobacco pipe that joins the bowl and the stem]. On unrolling it I found information that General Howe was coming out the next

morning with 5000 Men — 13 pieces of Cannon — baggage wagons, and 11 boats on wagon wheels." When the British marched out to Whitemarsh, the American forces were ready and waiting. Fighting ensued until the British retreated, calling it a draw. It was obvious someone had tipped off the Americans and several days later, the officer who had set up the meetings at Lydia's house paid a

call.

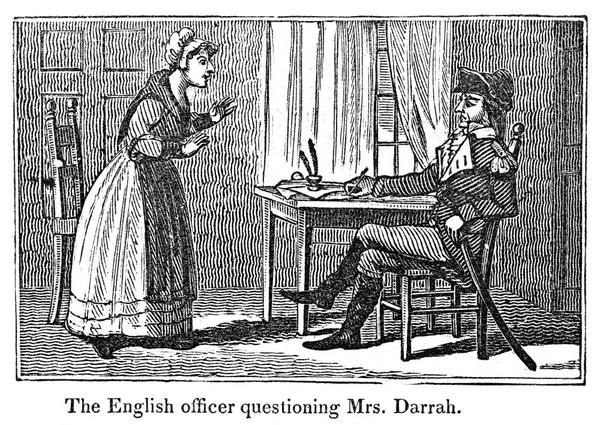

Lydia convinced the head of Britain's intelligence operations Major John Andre that she and her family had been fast asleep and heard

nothing. "One thing is certain the enemy had notice of our coming, were prepared for us, and we marched back like a parcel of fools,"

Major Andre said. "The walls must have ears." While we don't know the true facts of Lydia's spying activities or exactly how the message got to George Washington, it's important to note that in Eruopean wars fought at the time, when an army took control of the capitol city of an opponent, they

were presumed to have won the war. If George Washington's forces had been caught unprepared and suffered a loss at Whitemarsh, the rebel cause might well have been lost. Much is made of Lydia Darragh forsaking her pacifist beliefs to aid the cause of freedom and that had she been caught; she would have been hanged as a spy. In my view, she may have saved a nation, but her courage was most likely inspired by her desire

to save her son. I have no information about whether young Charles of the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment survived six more years of war. Lydia and William Darragh were buried in a Quaker cemetery not far from their original home in Philadelphia, but both lost their membership in the Society of Friends before the end of the war. We don't know for sure, but possibly their aiding the

American army became known in the local community, and they were no longer welcome.

Like my article today? Please share:

Major John Andre mentioned above as the head of British intelligence during the American Revolution is known for recruiting and handling the traitor Benedict Arnold and was himself

hanged as a spy after being caught with incriminating papers in his boots.

Location where American General Arnold and British Major John Andre plotted to surrender West Point. Located on the shore pathway south of Haverstraw in the historic

Dutchtown area.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|