June 28, 2024 Hello , Thirteen people protesting segregation left Washington, D.C., May 4, 1961, on two buses bound for New Orleans. They never made it. Ten days into the trip, one of the buses pulled into Anniston, Alabama and found an angry mob of Ku Klux Klan members ready and waiting. The KKK smashed a window of the bus and tossed in a homemade firebomb. Twelve-year-old Janie Forsyth saw the whole thing and that explosion presented her with a choice. The kind of choice you remember for the rest of your life.

Girl Crashes KKK "Surprise Party"

A civil rights leaders scouting the Freedom Riders' route from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans believed Anniston, AL would be "a very explosive trouble spot." He worried riders might not escape

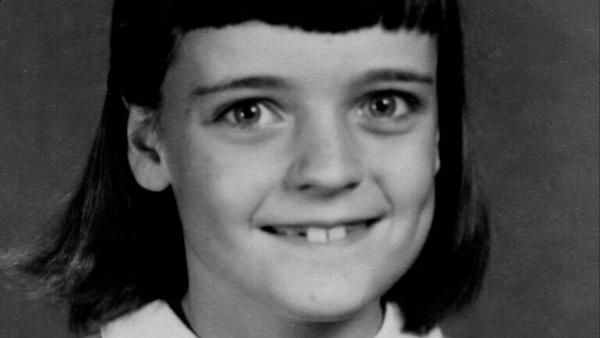

with their lives. Townspeople felt the pressure building, even youngsters like 12-year-old Janie Forsyth knew trouble was coming. She heard about it at the breakfast table. "My dad told my family 'those damn Freedom Riders' would be coming through town," she said. "And the

KKK had some kind of “surprise party” planned for them, and he kind of laughed. That woke me up." Janie had no idea the "party" would break out in her own front yard. "I could tell [Dad] knew more than he was saying, but I was afraid to pry. I didn’t want to even imagine my dad could

be a member of the KKK. I never knew if he was."

Janie Forsyth, Anniston, Alabama. Photo courtesy

PBS. The Greyhound bus rolling toward Anniston carried five regular passengers, two of whom were undercover state patrol

officers eavesdropping for the governor. Seven were Freedom Riders and two, journalists. The year before, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled

segregation on interstate transportation unconstitutional, but it was still the practice throughout much of the South. The Freedom Riders, mostly college students, challenged local law and custom by riding Greyhound and Trailways buses and trying to use “whites-only” restrooms and “whites-only” lunch counters in bus stations. They met with hostility along the way, but it reached a new level at the Anniston bus station. A mob of about fifty white men, dressed in their Sunday best having just come from church, attacked the bus with pipes, chains, clubs or whatever was to hand. They smashed windows, dented sides of the

bus and slashed tires. When police belatedly arrived, they made a show of clearing the crowd and escorting the bus out of the city limits.

The mob at the bus station followed in their own cars and trucks. Several miles west of Anniston, flat tires forced the bus to stop in front of the Forsyth and Son Grocery store.

Forsyth and Son Grocery. Photo courtesy PBS American Experience Janie heard the noise and came out to see what was happening. The crowd of people following the bus had grown to roughly two hundred. "Angry white men yelling racial epithets and armed with various bludgeoning implements milled around our front yard and the parking lot of our family’s grocery store next door. They surrounded the bus with obvious evil intent while their families — wives, children and babies in

arms — quietly watched. Janie, a self-described, shy 7th grader, had already developed a conscience. She believed her

favorite passages of scripture, "Whatever you do to the least of my brothers, you do it to me." "I was already a civil rights activist, intent on doing the right thing. I was just closeted about it." Then she saw a man break a window on the bus and throw something inside. "A crowd stood around him, trying to hide his identity, but I could see he was white. The “something” turned out to be a firebomb, and the bus burst into flames. Acrid black smoke soon billowed out the back window."

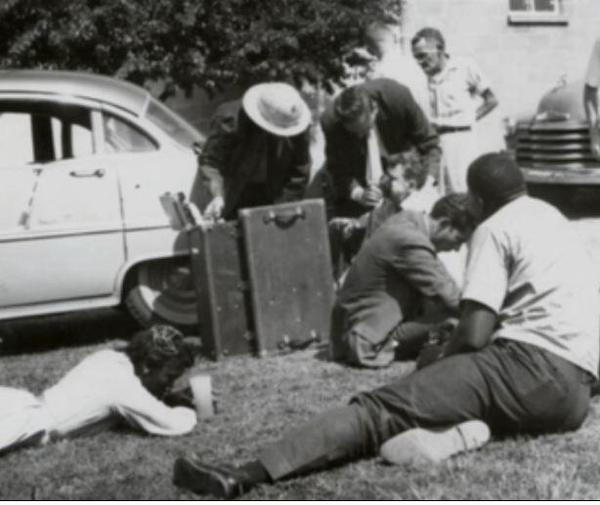

Anniston, AL, May 14, 1961. Photo courtesy U.S. National Park Service In a state of terror, passengers scrambled to flee the bus, some climbing out broken windows. The front door was held shut by Klansmen. People in the crowd shouted, "Burn them alive" and "Fry the goddamn n%#*&$s." Somehow, the mob was forced

back, possibly due to an exploding fuel tank or it could have been one of the law officers inside waving his gun. Riders managed to escape the bus, coughing and gagging in the tense smoke. The first to emerge was Henry "Hank" Thomas. "Are you all OK?" a man shouted, but then before Hank could answer, the man hit him in the head with a baseball bat. Thomas dropped to the ground, nearly losing consciousness.

Anniston, AL, May 14, 1961. Photo courtesy U.S. National Park Service. "The growling, cursing white men began to beat them," Janie Forsyth McKinney recalled as an adult. "I could hear the passengers cry out, “Water, please give us water … we need water. They were so sick by then they were crawling and puking and rasping for water. They could hardly

talk.” Janie ran into her house for a bucket of water and as many glasses as she could carry. She returned to push through the swinging clubs and snarling

bodies. "I knew what I was doing was dangerous," she said, "and it could get me in real trouble.... It seemed to [the whites] that the

blacks were penetrating some sort of barrier that they had no right to come through and sitting next to a person on the bus was the beginning of that barrier coming down and they couldn’t stand it.

"They weren’t ashamed of what they were doing, they thought it was a

social service…This is how to be a man…I’m protecting my women and children. They were proud of it."

Janie hurried to help a woman who looked like the nanny who raised her. "I took her a glass of water. I washed her face. I held her. I gave her water to drink and as soon as I thought that she was going to be okay, I got up and picked out somebody else."

Anniston, AL, May 14, 1961. Photo courtesy PBS American Experience. Local authorities allowed the violence to continue for 15-20 minutes before firing shots in the air to disperse the crowd. They made to effort to provide medical aid to the injured. Janie was told that Klan members considered charging her with a crime for getting in their business, but in the end decided was a mentally deficient child and let it go. "For years, various local KKK members railed against me, sometimes getting right in my face. In the hallways of my high school, the offspring of Klansmen often confronted me. But no one laid a hand on me. After the initial furor passed, my

family never talked about it again, as if I had done something shameful that would be best forgotten." Janie's choice to step out of place in southern culture

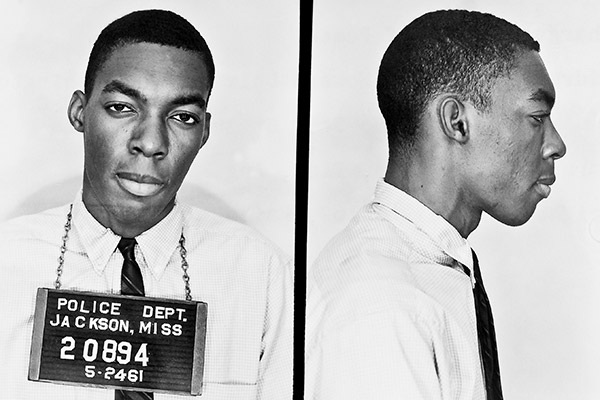

that day might have been lost to history, except for Hank Thomas. As the 20th anniversary of Freedom Summer approached, CBS news producers interviewed Hank about what happened that day in Anniston. He said they couldn't “do that story justice” without finding the little white girl who had given the Freedom Riders water. Thomas continued to participate in the Freedom Rides and was later arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, where he believed he would not survive.

Freedom Rider Henry "Hank" James Thomas

In Jackson, police routine arrested the civil rights activists as soon as they stepped off the bus, charging them with a breach of the peace. When local jails

filled up, the young people were sent to the infamous state penitentiary, Parchman. "We knew about Parchman, and we knew that if a black man was killed by a prison guard, people just shrugged their shoulders. It minimized the paperwork."

Thomas did survive his imprisonment, and in September 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission finally issued regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals. Janie said she never regretted her

choice that day to help those in need.

Like my article today? Please share:

Sources https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anniston_and_Birmingham_bus_attacks#cite_ref-:3_17-0 https://www.bbc.com/news/13533144

One of the few surviving veterans of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion has died at age 104. Romay Johnson Davis was one of the 880 female and all black Six Triple Eight posted to Birmingham England in 1945 to process an overwhelming backlog of

military mail. You can read all about it in my book Standing Up Against Hate.

Romay Johnson Davis served in the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. (Women Veterans Historical Project at the University of North Carolina at

Greensboro)

Before her assignment with the Six Triple Eight, Romay served stateside in the Women's Army Corps at Camp Breckinridge, KY, as a vehicle mechanic and a driver. “Women are as capable … as men are in their chosen positions,” she told People magazine in 2022, when she received the Congressional Gold Medal. “So if you give them more chance — and Black women especially, because they haven’t had the same opportunity — give them a chance and see what they can do. Ask them.” Thanks for your service, Romay. Rest in peace.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|