May 3, 2024 Hello , Albert Einstein might never have discovered E=mc2 if not for the proverbial woman behind him. His first wife Mileva Einstein-Maric not only kept his house in the traditional sense, but also kept him on track in his scientific work and there's some evidence she contributed to his discovery of the Theory of

Relativity. There is no doubt Mileva worked closely with Albert during the time of his most significant contributions to our understanding of space, time and motion, including in 1905, often called Einstein's miracle year. In that one year, he published his Special Theory of Relativity and four other papers that reshaped

modern physics and our understanding of nature. Some evidence suggests Mileva Einstein-Maric may have been an unrecognized co-author of Einstein’s 1905 relativity paper, or she may have been only a sounding board for his theories. Some scientific historians believe Mileva made little to no contributions to Einstein's work. Whatever the truth, Mileva's story resonates strongly with many women's experience even today, that of being undervalued and cast aside.

Did She? Or Didn't She? Einstein's Wife and E=mc2

Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić met and fell in love when they were students at the Swiss Polytechnic Institute in Zurich in 1896. A talented mathematician and physicist, she was the only woman in her class and only the fifth woman ever to be

admitted to the university. Mileva was born to an upper-class family in Serbia in 1875, fortunate in that her father supported her education, securing permission for her to attend the Royal Grammar School for Boys in Zagreb, where she was the only girl allowed to study physics. Ahead of her time, she declared, "I believe that a woman can have a career like a man."

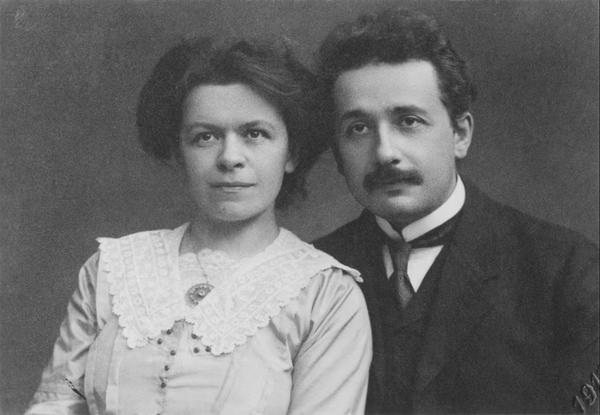

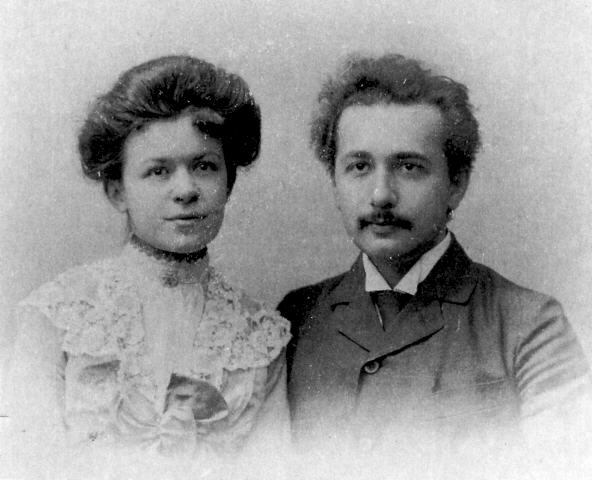

Mileva Marić, mathematician and physicist. Mileva was described as a quiet, clever girl with expressive dark eyes. Albert once wrote

that he was glad to have found a woman as strong and independent as himself. They became inseparable study partners, she methodical and organized and he creative. But early in the relationship, she feared her scientific studies might be sidetracked. In October 1897 she left Zurich for school in Heidelberg, one of the few universities in Germany that allowed women, though only

as guest students. She had to obtain prior permission of every professor whose course she wanted to attend. She and Albert wrote each other affectionate letters, Mileva enthusiastic about seminar with foremost physics and mathematics professors. They missed other and Albert urged her to return, which she did after one semester. The couple

continued their studies together, enjoyed walks in the city and hikes in the mountains, though they moved slowly due to Mileva's disabled foot. They both loved music. She sang Serbian songs and played the tamburitza, a South Slavic long-necked lute. Albert played the violin. He goes hungry to save money to take Maliva to the opera.

Maliva and Albert embarked on a "modern" love affair. We know something of their relationship from letters Albert wrote to Mileva during school holidays. The debate intensified in the late 1980s when previously unpublished letters between Einstein and Marić

were released These letters, first son Hans Albert Einstein, and his family in Berkeley, Calif. Forty-eight letters from Albert to Mileva survive and ten from her to him. In August 1899, Albert wrote to Mileva: “When I read Helmholtz [German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz] for the first time, it seemed so odd that you were not at my side and today, this is not getting better. I find the work we do together very good, healing and also easier.” Then on 2 October 1899, he wrote from Milan: “… the climate here does not suit me at all, and while I miss work, I find myself filled with dark thoughts – in other words, I miss having you nearby to kindly keep me in check and prevent me

from meandering.”

EINSTEIN, Albert (1879-1955) letter signed ('Ba') to his first wife, Mileva Einstein.

(Christies.com) Despite their Eastern Orthodox Catholicism, Maliva's parents were tolerant of the relationship, believing she'd have few

suitors due to her interest in academics and her disability. Albert's parents opposed, saying Maliva was too old [four years older], too bookish and a Serb, not a Jew. By the end of their classes at Polytechnic in1900, Mileva and Albert had similar grades (4.7 and 4.6, respectively) except in applied physics where she got the top mark of 5 but he, only 1. But when they both sat for the diploma exam, she failed to pass. Albert passed, though his scores were rounded up and hers down. For the following year Albert search unsuccessfully for a job, while Maric worked in a lab and studied to retake her tests. After a short holiday in Italy in May 1901, Mileva discovered she was pregnant. Even so, that July she tried again to pass her diploma exam and failed. Albert finally found a

low-paying job as a substitute teacher, but he started avoiding Mileva. She went home to her family in disgrace, though she took one trip back to Zurich in an

effort to and convince Albert to marry her. He refused. Mileva gave birth to their daughter named Liesel in January 1902. The couple reunites at some time

that year after Albert gets a job working for the patent office in Bern, Switzerland and they finally marry January 6, 1903, when Albert's father, on his death bed, gives his blessing. The fate of Liesel is unknown, the last mention of her is in a 1903 letter saying she had scarlet fever.

Mileva and Albert Einstein's wedding photograph, January 6, 1903. After their marriage, Albert worked long days at the Patent Office with only Sundays off and Mileva kept house for them. Their son, Hans-Albert, told historian Dord Krstić his

parents’ “scientific collaboration continued into their marriage, and that he remembered seeing [them] work together in the evenings at the same table.” Much later, Albert told American Physicist Robert S. Shankland relativity had been his life for seven years. Biographer Peter Michelmore, wrote that after spending five weeks completing the article that was the basis for the theory of relativity, Albert “went to bed for two weeks. Mileva checked the article again and again, and then mailed it”. In 1905, the year of Einstein's famous five papers came out, he said, "For everything I achieved in my life, I must thank Mileva. She is my

genius inspirer, my protector against the hardships of life and Science. Without her, my work would never have been started nor finished."

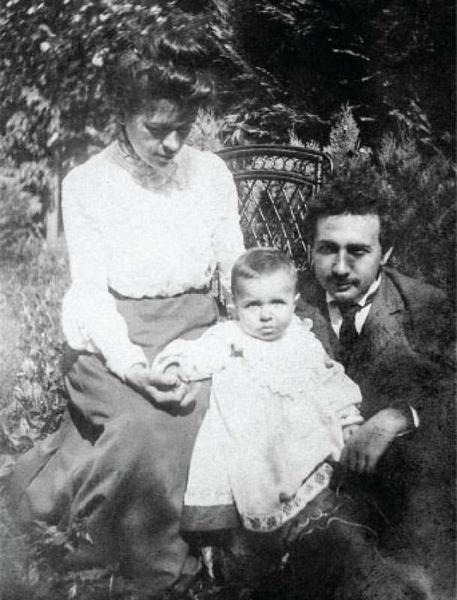

Mileva and Albert with their oldest son Hans Albert, born 1904, a second son Eduard was born

1910.

After Albert's letters to Mileva became public in 1989, historians started looking more closely at documentary material about their relationship and that's led to more debate about how much credit Einstein's first wife deserves for his work. If she co-authored his paper on relativity, why wasn't her name on it with Albert's? Radmila Milentijević, author of Mileva’s most comprehensive biography published in 2015 has a theory. Though Mileva was extremely intelligent and considered by Albert to be his equal, a woman of the time, raised in a patriarchal Serbian family, might sacrifice her own academic career and chance of

renown to work together with her husband to achieve something even greater. Dord Krstić, former physics professor at Ljubljana University, spent fifty years researching Mileva’s life. He says given the widespread sexism of the time; a paper signed by a women wouldn't be as highly respected. On the other side, Physics Historian Alberto Martínez writes, “I want her to be the secret collaborator. But we should set aside our speculative preferences and instead look at the evidence.” Whatever collaboration the couple had; it began to crumble sometime after Albert took his first academic position in Zurich in 1909. Eight pages of his first lecture notes held today in the Albert Einstein Archives in Jerusalem are in Mileva's handwriting. That September, she wrote her long-time friend Helene Savić: “He is now regarded as the best of the

German-speaking physicists, and they give him a lot of honours. I am very happy for his success, because he fully deserves it; I only hope and wish that fame does not have a harmful effect on his humanity.” Later, she added: “With all this fame, he has little time for his wife. […] What is there to say, with notoriety, one gets the pearl, the other the shell.” Three years later, Albert started an affair

with his first cousin Elsa Löwenthal and carried on a secret correspondence with her for the next two year.

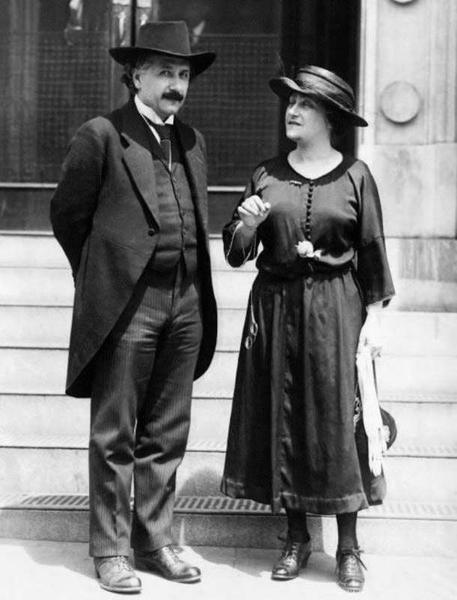

Albert with his second wife Elsa Löwenthal who escaped Germany with him, immigrating to the United States in 1933. Due to Albert's affair, Mileva moved back to Zurich with her two sons in 1914. She agreed to a divorce five years later, insisting in the settlement that she receive any money her might receive should he win the Nobel Prize. "Everybody knew Einstein was in line to win the prize and that in the postwar environment in Germany, this was a natural request from a wife who did not want a divorce and was suffering from depression," writes Galina Weinstein, an Albert Einstein Scholar and research associate at University of Haifa. American physicist Evan Walker Harris counters, “I find it difficult to resist the conclusion that Mileva, justly or unjustly, saw this as her reward for the part she had played in developing the theory of relativity.” Apparently, when Albert won the Nobel Prize, he said the money was his sons’

inheritance. Radmila Milentijević says Mileva strongly objected, writing to her ex-husband that the money was hers and considered revealing her contributions to his work. Albert's reply suggests perhaps his fame had gone to his head. "You made me laugh when you started threatening me with your

recollections. Have you ever considered, even just for a second, that nobody would ever pay attention to you says if the man you talked about had not accomplished something important. When someone is completely insignificant, there is nothing else to say to this person but to remain modest and silent. This is what I advise you to do.” Letter dated October 24, 1925 (AEA 75-364) While Albert became

cruel after the divorce, it's clear from his letters that he had respected her intelligence and been deeply in love. For a more intimate look at the love letters between Albert and Mileva check out this article by Maria Popova. Unless further documentation is discovered, we will never know for certain the true extent of Mileva's contribution to Einstein's groundbreaking work.

Like my article today? Please share by email or

Sources https://time.com/5551098/mileva-einstein-history/ https://www.inverse.com/article/31669-genius-einstein-mileva-maric-nobel-prize

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|