August 30, 2024 Hello , Born to Irish immigrants in Hannibal, Missouri during the Civil War, Mary Kenney knew the power or resistance from an early age. When nuns at her Catholic school tried to hold her back a grade, she refused to return, later

calling it, "my first strike." She reminds me a lot of Fannie Sellins, who I want to remember this week. August 26th was the anniversary of her killing in 1919, on the picket line Brackenridge, Pennsylvania by company hired thugs. Both women became widowed at a young age with young children to raise,

which happened a lot. But amazing for their times, both women were paid organizers for national labor unions, Fannie Sellins for the United Mine Workers and Mary Kenney, the American Federation of Labor (AFL). More on Fannie Sellins in the News and Links

section below, but first the story of Mary Kenney O'Sullivan. Back in the day, unions often banned women from membership, which led to Mary co-founding the National Women's Trade Union League in 1892, the first nationwide union in America dedicated to organizing working women. Mary also campaigned for women's right to vote and crossed paths, indeed, crossed purposes with the famed Susan B. Anthony.

"This Woman was Afraid of NOBODY"

Mary

Kenney and Susan B. Anthony shared a stage at Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, both women fierce in their passion for justice and women's equality. But Susan was a Grande Dame, campaigning for women's rights when Mary was still a babe in arms. She was single-minded, believing when women could vote, other rights would follow.

Mary Kenney

O'Sullivan, Schlesinger Library Radcliff Insitute, Harvard University.

The two activists arrived at the world's fair lecture hall on a hot, sultry August evening, the room baking like an oven and the windows too high to reach. The janitor refused to open them, and Mary suggested they appeal to the manager, and he didn't

want to help either. Later, Mary described what happened. “Miss Anthony had always been opposed to

unions and strikes. Her subject that night was “Suffrage” and mine was “The Value of Labor Organizations” suggested...that we refuse to speak till the windows were opened. They agreed and we had our way. I couldn’t resist the opportunity of reminding Miss Anthony that we had just won a strike." Mary speaking up to Susan B. Anthony impressed Historian Michele Steinberg, who says,

“This woman was afraid of NOBODY.” Back in Hannibal, MO, Mary

had gone to work at age 14 when her father died, leaving her to support her disabled mother. To start, she earned $2 a week at a book bindery. Within four years, she rose to supervisor, earning $5 a week, and when the company moved to Keokuk, Iowa, she followed, relocating her mother. Ten years later, when the book bindery went out of business, Mary's wages had increased to $11

for the six-day week. She'd spent nearly half her life with the company, and never had a day of vacation.

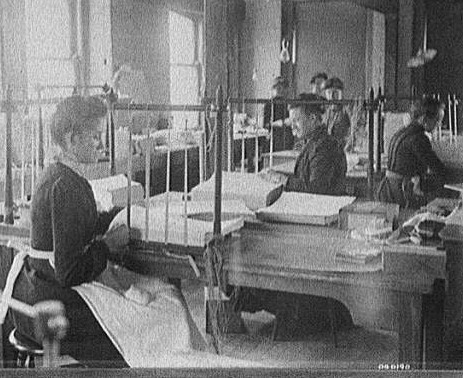

Bookbinding, Richmond & Backus Co., Detroit, Mich. circa 1900-1910.

Moving

north to Chicago, she easily found a job in the book binding industry, but the pay was only $7 a week, and Mary discovered men in the same job earned $21. So began her activist career. She organized women bookbinders in Chicago and started The Women’s Bindery Union no. 1. Even as unions organized in the 1890's, conditions for immigrant families remained deplorable. “She was appalled at the squalor of the city, ‘the tragedies of meagerly paid workers, the haunting faces of undernourished children, the filth."

Mary joined Jane Addams in her work at Hull House, which had become an oasis in the slums.

Younger children arts class, often facilitated by teenage or younger resident artists, c. 1922. Photo

from the Chicago History Museum. Jane Addams and Hull House were pioneers of social reform in the United States, offering housing and practical help to Italian,

Irish, German, Greek, Bohemian, Russian Polish and Jewish immigrants in the crowded, poverty-stricken Halstead area of Chicago. Hull House started as a kindergarten,

then expanded to offer daycare for working mothers, English and citizenship classes; theater, music and art classes; cooking, sewing and technical skills; and American government classes and an employment bureau. The settlement house brought together middle- and upper-class women reformers with working class women and important collaboration as Mary continued organizing for labor unions. She was steadfast in her efforts for equal pay, but it wasn't easy. "To say that it is difficult to organize women is not saying the half.... they are reared from childhood with one sole object in view — an object I do not wish to discourage but to elevate from its present conditions — that is, marriage. If our mothers would teach us self-reliance and independence, that it is our duty

to depend wholly upon ourselves, we should then feel the necessity of organization." Mary worked to get Chicago's female bookbinders admitted to the

American Federation of Labor and was elected a delegate to the Chicago Trades and Labor Assembly. In 1892, she was hired as the first paid woman organizer for the American Federation of Labor. Working a short stint in New York City, she organized garment workers, printers, binders, carpet weavers and shoe workers. Relocating to Boston in 1894, Mary met and married John F. O’Sullivan, labor editor for the Boston Globe.

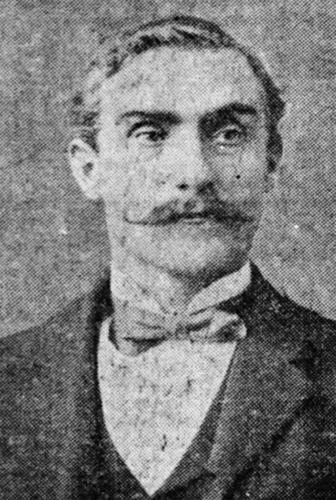

John F. O'Sullivan, Boston Globe photo, 1902. The couple had four children, their firstborn son, dying of diphtheria. Mary continued her work in the labor struggle, organizing women in Boston and depending on her husband to help with the home and

children. Their marriage ended in gruesome tragedy after six years when John was hit and killed by a train. He was well-known in the labor and newspaper circles in Boston and

the accident made headlines.

The Boston Globe, for which O’Sullivan worked, wrote:“The greatest sympathy for the widow of Mr. O’Sullivan is felt, and though bearing up bravely under the terrible affliction that has befallen her, her friends are deeply concerned for her

welfare.”

Mary later spoke publicly about this difficult time in her life and how she suffered a breakdown and went to a sanitarium for treatment. A year later, she was back on her crusade for women's rights.

A young widow and single mom, she co-founded the National Women’s Trade Union League in 1903 and served as it's secretary for nine years. The NWTU brought together diverse groups of women, including white educated reformers like Eleanor Roosevelt and Jane Addams and

immigrant workers like Rose Schneiderman, and Clara Lemlich.

Leaders of the Women's Trade Union in 1907. Shown from left to

right

are Hannah Hennessy, Ida Rauh, Mary Dreir, Mary Kenney O'Sullivan,

Margaret Robins, Margie Jones, Agnes Nestor and Helen Marot.

The cooperation Mary fostered between wealthy, professional and working women allowed them to lobby successfully, not just for higher wages, but

legislation in Massachusetts for a minimum wage and safety in the workplace for women and children, as well as to raise awareness of their exploitation. In 1906, Mary

addressed a committee in the U.S. House of Representatives in support of the Constitutional amendment giving women the vote. Women are producers in American society, she argued, and every producer should have the right to vote. Mary lived to see women passage of the 19th Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote, and also saw the birth of the US Department of Labor. At age 50, she was appointed factory inspector for the department, giving her the power to enforce the laws and standards she had worked so many years to attain for women. She held the job for 20-years until she retired at age 70.

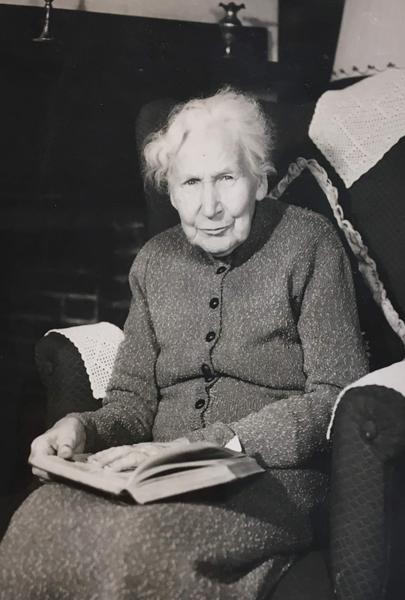

Mary Kenney O'Sullivan, circa early 1940s. After her death at age 89, Mary Kenney O'Sullivan was remembered in her eulogy thus, "She endeared herself to all who knew her by her rich nature, vigorous and outgoing, generous, humorous, tempestuous and loyal, by her capacity for never flagging devotion, spontaneous and without thought of credit or reward, her love

of life and of people of every sort, rich and poor equally."

Like my article today? Please share:

In

the heat of late afternoon August 26, 1919, Fannie Sellins arrived at the picket line near the entrance of Allegheny Coal and Coke in Brackenridge, PA. The five-week strike by United Mine Workers had been peaceful, but tense. Union pickets lined the public roads near the mine and the sheriff had sworn in extra deputies, passed out rifles and sent the men to patrol company boundaries. Near supper time, Fannie saw an argument break out between deputies and striking coal miners. She saw deputies beating a man with black jacks and shooting over the heads of the crowd to keep people back. “Stop, before someone gets hurt!” Fannie shouted, herding a group of children toward behind a fence to safety. “Stop!” She shouted again and three deputies fired at her, hammering Fannie to the ground. She died of the scene, as did the miner beaten Joe Strzelecki. Remembering Fannie's courage this week and her love for working people. Read her story in my book Fannie Never Flinched.

Booklist Starred Review ⭐ "The author may be

addressing this stirring story of early union activist Fannie Sellins to middle-schoolers, but the rigor of her approach yields a book with solid scholarly features….Her story, richly illustrated with vintage photographs and documents, fairly leaps off the page, driving home the message that the work she fought for is far from over." Publishers Weekly Starred

Review ⭐ "Over six brief chapters, Farrell deftly places Sellins’s story within the larger context of immigration and industrialization at the time."

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|