September 20, 2024 Hello , I wrote you about Luisa Moreno a few years ago, but never has her story been more relevant than now. I've brought it back for you in a new and more detailed edition. Feel free to forward this email to friends

and family. Born Blanca Rosa Rodríguez López in Guatemala in 1907, her father was a powerful coffee grower and her mother a socialite. She was educated by private tutors and sent to the United States for high school at the College of Holy Names in Oakland, California. She left her wealth and privilege behind to become a modern woman. She ended up changing her name to Luisa Moreno and fighting for the rights of workers and immigrants. Called a "parasitic menace" by her detractors, Luisa was driven out of the United States of America. In 1940, she spoke eloquently about the value of Mexican immigrants. "These people are not

aliens. They have contributed their endurance, sacrifices, youth and labor to the Southwest. Indirectly, they have paid more taxes than all the stockholders of California's industrialized agriculture, the sugar companies and the large cotton interests, that operate or have operated with the labor of Mexican workers." Rosa's story is an inspiration and an invitation. She cast off the expectations of a woman in her time and place, not knowing where her choices would take her. When sticking to her ideals got tough, she got tougher.

When sticking to her ideals got tough, Luisa got tougher

Blanca Rosa Rodríguez López returned home after her schooling in America hoping to attend the

University of Guatemala. In the 1920s, the school didn't admit women. Rosa rallied a group of upper-class debutantes to campaign for their right to be educated, petitioning and lobbying until the university eventually opened its doors to women. Rosa could have been the first

to enroll, but at 19, she ran away to Mexico City. "Rejecting her

family's wealth, and undoubtedly the limited expectations it imposed," says Historian Vicki L. Ruiz,

Rosa enrolled at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and became a journalist for a Guatemalan daily newspaper, living out her feminist ideals. "The woman continues to be attached to ignorance; her emancipation is necessary," she

wrote. "Feminism will make her become Conscious…and…by obtaining an adequate education, she will be prepared [for]…a much more ambitious future." Rosa wrote poetry and became a 1920's "flapper" in the avant-garde circle of Diego Rivera and

Frida Kahlo, enjoying the renaissance emerging in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.

Luisa Moreno in Mexico City in 1927. Courtesy Vicki L. Ruiz.

Rosa immigrated to the United States with high hopes in 1928, with no way of knowing the American Dream was about to crash. When the Great Depression hit the following year, "The well-heeled teenage feminist intellectual and poet who lived in the capital cities of Guatemala and Mexico in the 1910s and 1920s," as Historian Vicki L. Ruiz described her, found herself, living in a crowded tenement in Spanish Harlem. Rosa worked in a sweatshop eking out a living for herself, her unemployed husband and newborn daughter. Conditions were so poor; Rosa witnessed rats chewing the baby of a work friend and was compelled to organize a garment union local to try and improve conditions.

The following year, working as a waitress Zelgreen’s Cafeteria in New York City, Rosa joined a strike for the first time, protesting long hours and constant sexual harassment. When she tried to block the door of Zelgreen's, she was grabbed by police and ended up with a bloody injury to her face. Over the next 20 years, this tiny five-foot woman would stand tall for workers across America. In 1935, the American

Federation of Labor hired her to organize cigar-rollers in Florida, where she broke from her privileged past by changing her name to Luisa Moreno. She organized sugar cane workers in Louisianna, cotton pickers in Texas, beet harvesters in Colorado and tuna-cannery

workers in California. The newly formed United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), an arm of the CIO, hired her in 1938, to run a strike by pecan shellers in San Antonio. "[Luisa was] a formidable

and charismatic speaker in both English and Spanish. She wrote very well, and bilingually; she turned out the best written leaflets I’ve ever seen…she had a powerful gift for persuasion," said a longtime friend of Luisa's. "She could convince others by the weight of her logic, her ease of words, and her speaking abilities."

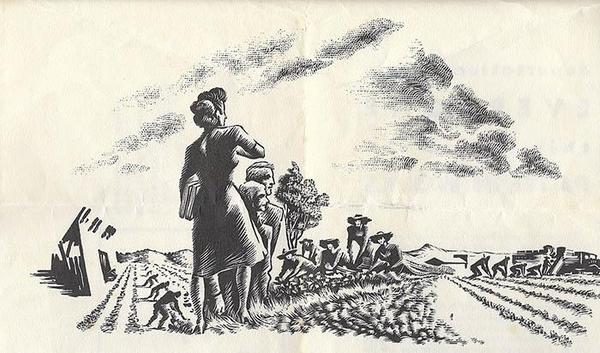

An illustration of Moreno as a labor leader, part of the pamphlet "The Case of Luisa Moreno Bemis."

printed to rally national attention and halt her deportation, around 1949. courtesy Vicki L. Ruiz. Luisa was a skilled labor organizer, the first Latina vice president of a union, but she saw wider and deeper issues. When Under a Texas Moon (1930) opened at a New York City theater with the tag line: Don Carlos Lies His Way into Women's Hearts and Laughs and Fights His Way Out, Cuban and Mexican students protested. They picketed the theater because of the movie's offensive portrayal of Mexican women. Police arrived, attacked the protesters and killed the leader, a student name Gonzalo González.

Luisa joined in the huge protest that followed, Cubans, Mexicans, Central and South Americans in New York uniting to condemn the murder and police brutality. This experience motivated Luisa's work to unify Spanish-speaking communities, as well as

workers. She founded the first national civil-rights assembly for Latinos: El Congreso de Pueblos que Hablan Español (the Congress of Spanish Speaking Peoples). In 1938, El Congreso was ahead of its time, calling women's equality and giving women leadership positions.

Luisa_Moreno, Fair use,

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74828739

When WWII started, the defense industry offered a huge number of well-paying jobs in California, particularly in the Navy town of San Diego. But Mexicans were prohibited from employment in the petroleum industry, shipyards, and other war-related

fields. Luisa spoke out against this discrimination. "California has become prosperous with the toil and sweat of Mexican immigration attending to its number one industry, agriculture. Now [Mexican migrants] have sustained a true and lasting patriotism to a democratic country that refuses to give them citizenship or even basic civil rights." In 1947, Moreno went into semi-retirement in San Diego, though she started a chapter there of the Mexican Civil Rights Committee. She warned against racial profiling, stereotyping and police brutality against Mexican Americans and other ethnic minorities. Amid paranoia engendered by the Cold War, Luisa was stunned to find herself targeted by immigration officials. The FBI offered her US citizenship in exchange for her testimony against International Longshore and Warehouse Union leader Harry Bridges, who was accused of being communist. She refused. Then one day she noticed her

gardener, Manuel, peering through a window into her office, apparently trying to read the titles of books on her shelves. He claimed he wanted to ask her about the placement of some plants, but Luisa pressed him. Manuel admitted the FBI had pressured him to find incriminating evidence against Luisa. In exchange, they offered American citizenship to his family. Manuel confessed he'd

been questioning her neighbors and friends about her reading habits, whether she appeared to living “beyond her means" and they believed she was loyal to America. She advised Manuel to do what he had to safeguard his family and kept him on as her gardener. But she and her husband destroyed documents of books they feared might be used against them. California State Senator Jack B. Tenney, of Los Angeles, branded Luisa a “parasitic menace” and had her subpoenaed to appear before the California State Senate Committee on Un-American Activities. He finagled her deportation as a “dangerous alien” in 1950. Luisa Moreno returned to her native Guatemala but was

forced flee when the C.I.A. helped the Guatemalan coup d'état in 1954 that deposed the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz. In her later years, Luisa was able to return to Guatemala where she died November 4, 1992.

Like my article today? Please share:

Sources https://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/2011/jun/22/unforgettable-california-whirlwind-part-one/

I wrote awhile back about another incredible Latina labor organizer who led a strike by San Antonio pecan shellers, Emma Tenayuca.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|