August 1, 2025 Hello , We think of the Crusades of the middle ages as holy wars where European knights and noblemen traveled to the Middle East to wrest the Holy Land from Muslim people who had controlled it for centuries. What I didn't understand is how the Crusades decimated woman's rights. The Crusades cast a shadow over international relations in the Middle East that still darkens the world today and is at the root of religious intolerance and xenophobia in the United States. They holy wars also determined ideas about women's place in the world that would hold sway for centuries to come. Byzantine Princess Anna Comnena was there, reporting live on the First Crusade, so to speak, and the beginning of a long, dark period for women now poised to return.

Byzantine Princess and Historian: Anna Comnena

Anna Comnena was the daughter of Alexios I Comnenus who ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1081-1118 CE. As his first born, she was in line to become the Empress of Byzantium. She had role models, women rulers like Irene of Athens (c. 752–803) and she became perhaps the the best-educated woman in the Mediterranean world between the 5th and the 15th centuries. Byzantine women were the fore-mothers of modern liberated women. They had rights and privileges unknown in other societies and were active in government, medicine, and education. Anna learned Greek literature, Aristotle and Plato’s philosophies, mathematics, rhetoric, astronomy, geography, science and religion. She had her own money, political opinions and complete freedom. As the princess, she had more opportunity other women and contributed to her community by teaching medicine and overseeing an orphanage and hospital designed for 10,000 patients. No portraits survive of Anna. But we can make some guesses about her appearance.She was Armenian and said to have large dark, lively eyes, a round face and figures lithe and energetic. Maybe she looked like this woman portrayed in a Byzantine mosaic.

Fragment of a Byzantine Floor Mosaic, Byzantine, 500-550

CE. Photo By Sailko - Own work, CC BY 3.0 When Anna was eight,

like many little girls, she was disappointed by the birth of a baby brother. But she had more reason than most. Her brother John II was designated heir to the throne and Anna's place cast aside. She continued her education and preparation for a woman of the royal family. When Anna was a teenager, her father Alexius was stymied by Turkish raids on his undefended southern and eastern borders. His reign had brought order after a period of chaos and disaster that reduced the Byzantine Empire to just one of the states in an increasingly fragmented Middle East. Now, Alexius turned to Pope Urban II for help and subsequently the pope instigated a military campaign by western European forces to recapture the city of Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control. But when tens of thousands of European soldiers arrived to

defend the magnificent city of Constantinople, Alexius found they had no intention of taking orders from him. Indeed, what came to be called the First Crusade (of at least eight major/intermixed with many more minor) was merely the beginning of the end for the Byzantine Empire and the rights and freedoms exercised by women under its rule. At the time of the First Crusade, 1095–1099, Anna was quite well aware of what was going on. Neither she nor her father would live to see the Fourth Crusade when the

unimaginable happened. Constantinople, one of the world’s most magnificent cities for nine centuries and the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, was ruthlessly sacked. Not by it's Ottoman enemies, but by western Christian soldiers.

The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople (Eugène Delacroix, 1840). The most infamous action of the

Fourth Crusade was the sack of the Orthodox Christian city of Constantinople. I'll get back to Anna and her singular contribution to the history of the

Byzantine Empire, but first, let's take a moment here. Prior to and after the Fourth Crusade, Western Europe’s rulers—ostensibly Christian, but deeply

patriarchal—systematically stripped women of their legal rights. Laws that had protected women’s property and bodily autonomy were replaced by codes that treated women as perpetual minors, subject to the authority of fathers or husbands. The right to own property, to inherit, to speak in court, even to control one’s own children—these were swept away. As the West expanded, it carried these new, restrictive policies into every land it conquered. The legal erasure of women became a defining feature of Western law, echoed in colonial policies and, later, in American and European legal systems. The Byzantine tradition of women’s agency was forgotten, buried under

centuries of systematic patriarchal cultural and government structures. Anna Comnena was rolling in her grave! She did not give up her own political power easily. At 14, in 1097, she married an aristocrat and spent years plotting to get him proclaimed emperor. When John II took the throne after her father's death, she went so far

as to hatch a plan to murder her brother. All was set, the guards bribed, and Anna's husband tasked with giving the signal to move, but he could not go through with it.

The plot failed and it's amazing her brother didn't execute Anna, but merely confiscated her property. After that she gave up her public life and political aspirations.

At the convent her mother had founded, Kecharitomene (Our Lady of Grace) Anna gathered philosophers and men of letters and organized a sort of salon. When her

husband died, she retired to the convent and it was there, in the last years of her life, she made her indelible mark on the world Anna wrote a thorough record of her

father's reign and the first Crusade.

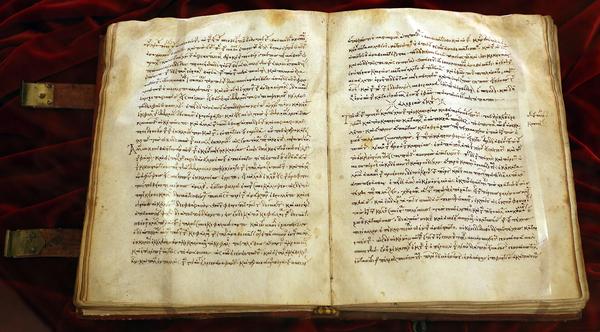

12th-century manuscript of the Alexiad in Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence,

Italy. Photo from Wikipedia In the quiet of the convent, she wrote the Alexiad, a 15-volume chronicle of her father's reign openly

patterned on Homer's Iliad. She poured into its pages the drama of her family, the devastation of the Crusades, and the complexities of Byzantine politics. She wrote

not as a passive bystander, but as a participant and critic, defending her father’s legacy and challenging the narratives of Western chroniclers who painted Byzantium as decadent and weak. Her voice is sharp and passionate, perhaps still bitter over her loss of the throne. “I am aware that I am a woman, and that it is not proper for me to concern myself with these matters," she wrote. "But I have written what I have written, and I will not be silent.” To Anna, the European crusaders appeared as uneducated barbarians with no sophistication or even manners. Worse, they did not arrive as saviors against the Muslim threat, but as looters and destroyers. Norman and Frank soldiers, amazed at Byzantine brocades, jewels, and magnificent works in gold or enamel, rallied behind leaders who envisioned taking the eastern empire for themselves.

The Horses of Hippodrome of Constantinople that are now in St. Mark’s Cathedral, Venice,

Italy. Anna wrote about how her father diffused conflicts between these rough-hewn army generals and protected his own interests. Today historians regard

Alexius as one of most capable rulers, military commanders and diplomats of the Byzantine Empire The Alexiad is considered the main source of Byzantine political

history from the time period, and the only contemporary account of the First Crusade from a Byzantine perspective. It also details daily life at the court, internal plots and intrigues, wars and invasions, and religious heresies. Historians believe Anna Comnena was the first female historian. Her words still ring true today. “The stream of Time, irresistible, ever moving, carries off and bears away all things that come to birth and plunges them into utter darkness, both deeds of no account and deeds which are mighty and worthy of commemoration... "Nevertheless, the science of History is a great bulwark against this stream of Time; in a way it checks this irresistible flood, it holds in a tight grasp whatever it can seize floating on the surface and will not allow it to slip away in the the depths of Oblivion.” -Alexiad opening as translated by E.R.A. Sewter Anna died at the convent at age 70–72, sometime between 1153 and 1155. The Crusades are remembered as holy wars, but they were a complicated mix of religious fervor, political ambition and economic interests that have modern parallels if we choose see them. Similarly, we often see women's rights as a modern invention, but the truth is more complicated—and more inspiring. The Byzantine woman remind us progress isn’t linear. Rights have been won, lost, and won again. The struggle for women’s autonomy is as old as civilization itself and yet never

assured. What would our world look like if the Byzantine model had prevailed in the West? What can we do today to preserve women's rights? Let me know what you think.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources Anna Comnena (1083–1153/55) | Encyclopedia.com https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1273/the-crusades-consequences--effects/

I spend my off hours in the garden where I contend with one problem after another. Something is eating at the root of my bush beans, something else nibbling at my kale and the 90-plus degree weather is causing the blossoms to drop from my

tomatoes. But I'm getting lots of cucumbers and enjoyed the last of my baby beets in a salad. Invested in some shade cloth and hope I'll soon have ripe tomatoes.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|