2025 Hello , From it's very birth, Richmond, Virginia has been getting rich on tobacco. A recent feature article in Richmond Magazine Built on Smoke illustrates this with a timeline from the 1700s to present day. It makes no mention of the Black women who processed the tobacco. In the 1930s, when the Richmond Tobacco Strike changed the landscape of the industry, the timeline mentions only that Lucky Strike became America's most popular cigarette. Black women rose up to demand better pay and working conditions in a series of strikes lasting nearly four years. In the former capitol of the Confederacy, they faced off with tobacco industrialists and won. Today, they're barely a footnote in the city's history. It unlikely any school children in the country learned about Louise "Mamma Lou" Harris, the women at the center of the fight, in which, or course, the police were on the side of the companies, not the workers. Mamma Lou Harris claimed, “They [Police] ‘fraid of the women. You can outtalk the men. But us women don’t

take no tea for the fever.” Read on. Bring Mamma Lou Harris and the Black women tobacco stemmers of Richmond out of the shadows. After all, Richmond would

not have been rich without them.

With No Hope of Help They Helped

Themselves

By the mid-1930's slavery has been outlawed for sixty years, but in the former

capitol of the Confederacy some things had hardly changed. For one, the tobacco factories, leaky roofs, rooms dim, damp and moldy, choked with tobacco dust, no ventilation, no drinking water, no lunch rooms. Workers had to drink from the water boilers and eat lunch in the restrooms. The factories still operated like plantations, the hiring practices little different than slave auctions. “Foremen lined us up against the walls,” remembered one tobacco stemmer, “and chose the sturdy, robust ones.” Once hired, the women discovered sexual harassment and assault from foremen and supervisors became routine and constant. “We had a ‘straw boss’ and as many women as he could get to go back in the ‘hole’ with him during the daytime, he got ‘em," said Florence Walker a Richmond stemmer. "Just having sex is what it was, and some girls would go. I told him I wouldn’t and one day he handed me a slip

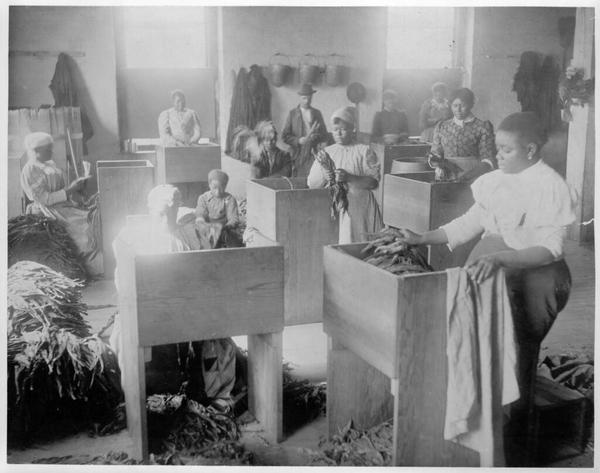

and told me ‘You don’t have any more job.’ We had absolutely no protection… they fired you when they got ready… and treated you any kind of way, and there wasn’t anything you could do about it.” Pictured below is a cleaned up display of a tobacco factory reportedly displayed at the Paris Exposition of 1900.

Sorting tobacco at the T. C. Williams & Co., tobacco, Richmond, Virginia.

Reportedly displayed as part of the "American Negro Exhibit" at the Paris Exposition of 1900. (Image: Public Domain) Tobacco stemmers often worked 80 hours a week, earning piece-work wages that paid between five and six cents per pound of stems pulled. An experienced worker could pull the leaves off the stems fast enough to earn twelve and a half cents an hour. Louise Harris started worked at the I.N. Vaughan Export tobacco stemmery in 1932. Her first day on the job she realized “preachers [didn’t] know nothing about hell. They ain't worked in no tobacco factory.” In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal passed Congress to get American workers on their feet after the 1929 crash and resulting depression. The legislation secured a forty-hour workweek, a

minimum wage, worker's comp, unemployment compensation, Social Security and health insurance. Guess what. The New Deal was no deal for the

Black women tobacco stemmers. None of the provisions extended to agricultural workers in the South. There was a union, the Tobacco Workers

International Union (TWIU). But guess what. The TWIU organized around occupations, which was de facto racial segregation. The union ignored African-American workers and especially Black Women who worked on the very bottom rungs of tobacco production. Union activity also ran the risk of stirring up the Klu Klux Klan. Maybe when you have no hope of anyone showing up to help you, that's when you gain the courage to help yourself.

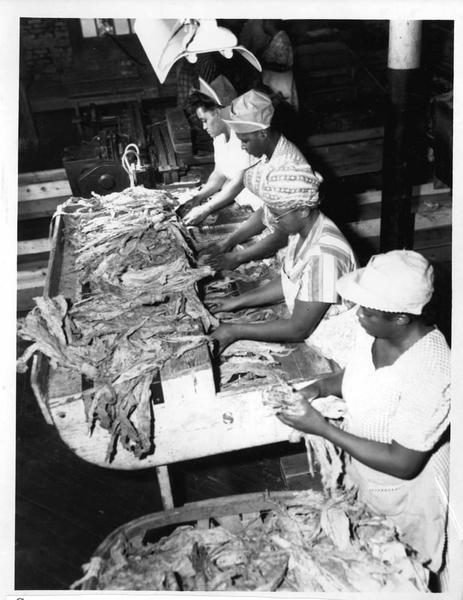

Many African American women in Durham, N.C. worked as tobacco stemmers. Image courtesy of the Durham

Historic Photographic Archives. On April 16th, 1937 stemmers at the Carrington and Michaux (C & M) tobacco plant couldn't stand their working conditions

any longer. They walked off the job in protest. The woman had no knowledge or experience about union organizing, but when they reached out to the TWIU, the timid

union would not endorse a strike that would shake the foundations of Jim Crow society. But it so happened the newly formed Southern Negro Youth Congress (SYNC) had held

second conference in Richmond that year. Several young men in the group, experienced labor organizers, helped the women organize a new union, the Tobacco Laborers and Stemmers ,(TWIU), draft their list of demands and present them to company management. Within 48-hours the company agreed to a wage increase, an eight-hour-day/40-hour-week, and collective bargaining recognition. It was a huge victory that sparked strike fever across the tobacco industry in Richmond.

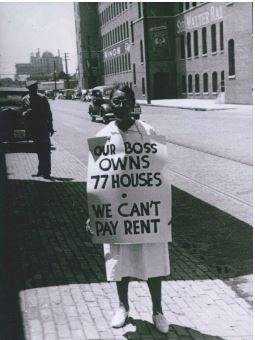

Unidentified tobacco worker picketing on the 900 block of N. Lombardy Street, Richmond, Virginia, 1938. Library of Congress. (Photo accessed August 14, 2025)

Louise Harris had put up with "hell" for six years at the I.N. Vaughan Export stemmery in Richmond VA. She and

the other women at Export were some of Richmond's poorest workers, using tobacco burlap for blankets in the winter. A male co-worker had been giving Louise a hard time since

the day she was hired.Then one day he shouted insults at her as usual and she shouted back, “giving him a tongue-lashing”. He accused her of being involved with the union. She wasn't. But it was good idea and she showed up at the next meeting with 60 of her co-workers. "When they asked for volunteers to organize Export, I can’t get to my feet quick enough…And then on the first of August, 1938, we let ‘em have it. We called our strike and closed up Export tight as a bass drum." Louise gained the nickname "Mamma Lou" as the picket captain leading five hundred strikers. "[T]his scab came up with a couple hundred others and tried to break our line, but we wasn’t giving… a dog a

bone." The factory owner lasted 17 days before admitting times were changing and agreeing to bargain with the union. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was watching, saw Louise's leadership pay off and invited her to work with a newly established Tobacco Workers Organizing Committee. Soon she was known by a new

name, Missus CIO Richmond. But on Google Images, there is not one picture of Louise Harris, Mamma Lou Harris or Missus CIO Richmond. She's barely mentioned at

all.

The Crisis, magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in a 1938 article described the women as needing men's guidance, as “toiling,

illiterate, leaderless...[with]no conception of struggle…. tired and worn looking, dressed in the pathetic and incongruous Sunday best of underpaid workers.” Two years later, The New Republic profiled Mamma Harris. In possibly the only article about the strikes to focus on her there was no mention of her brilliance, organizing abilities, or curiosity––those words described the men helping organize

the strikes. Rather, Mamma Harris was a “scrawny hardbitten woman...[from a] “tenement in Richmond’s ramshackle negro section.”

Yet, it was the woman making the day-to-day operations of the strikes successful. Her husband Bennie, quoted more than she in the profile, said as much. “There was five hundred of the women on the picket line and only twenty of us men”

In the Jim Crow era, Richmond’s tobacco strikes required courage, strategy and organizing skill. They changed the state of the industry and

improved the lives of thousands of women. The men involved are well-documented. Louise Harris, the only leader who actually worked in a tobacco factory, is but a

footnote.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources Louise "Mama Lou" Harris quotes from, The New Republic, November 4, 1940.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|