May 2, 2025 Hello , Mary Eliza Mahoney broke race barriers and helped shape the entire nursing profession. I'm telling her story as a kick-off to National Nurses Week in the US, which begins Monday. The advancement of medical science

in the 19th Century, opened another opportunity for women to perform long hours of hard work taking care of other people. But it offered them a skilled profession

and more autonomy. Hospitals reinvented themselves, no longer sources of medical care for the poor, they became sites for skilled health care. The best to be found. Trained nurses became central to this mission. At hospital schools, women found a place to defy social convention and gain scientific knowledge. Nursing education offered a route to higher pay, independence, and more power and authority in health care and their broader communities. In 1879, the first American Black woman graduated from nursing school and became a licensed professional nurse. She didn't bask in her personal accomplishment. She used her success to launch DEI in the nursing profession. There was nothing "woke" about it. Any kindergartner could tell you. Things just weren't fair.

How Mary Eliza Mohoney Embedded DEI in the Nursing Profession

Mary Eliza Mahoney stood only five feet tall and weighed less than a hundred pounds, but she made giant strides to carve out space for black women in professional nursing and her legacy remains vital

today.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs

and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Mary Eliza Mahoney, pioneer professional nurse" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1879.

She was hardly the first Black nurse in America. African woman practiced the healing arts from the time they arrived on these shores and passed

down their knowledge and skill through generations. But there is scant record of them. Even the few names we know from written accounts are obscure references like

“Nurse Flora,” “Old Sarah,” “Mammy Rachel,” or simply “an old Brown woman.” Black healers, nurses and midwives, both enslaved and free, held respect in their

communities for their ability to treat illness and injury. They devised natural remedies from herbs and foods brought from Africa, like black-eyed peas, sesame, and yams. Okra leaves made fine healing poultices. Met with new diseases, they experimented with local plants and widened their knowledge.

White families

used their remedies but gave them vague names like the "African Cure" or "Caesar’s antidote," rarely acknowledging the healer behind them. Though Black healing practices worked, white doctors often rejected them as unscientific. When they did record Black remedies, they renamed the herbs in Latin, erasing the original African knowledge and hiding the role of Black healers from the history of health care.

For hundreds of years, black women's medical knowledge was often dismissed, discredited or worse—when they were put to death as witches. Of course, black women also learned western nursing skills. Same as Florence Nightingale, a British nurse from Jamaica, Mary Jane Seacole nursed soldiers on the battlefront of the Crimean War and helped bring nursing into the modern age.

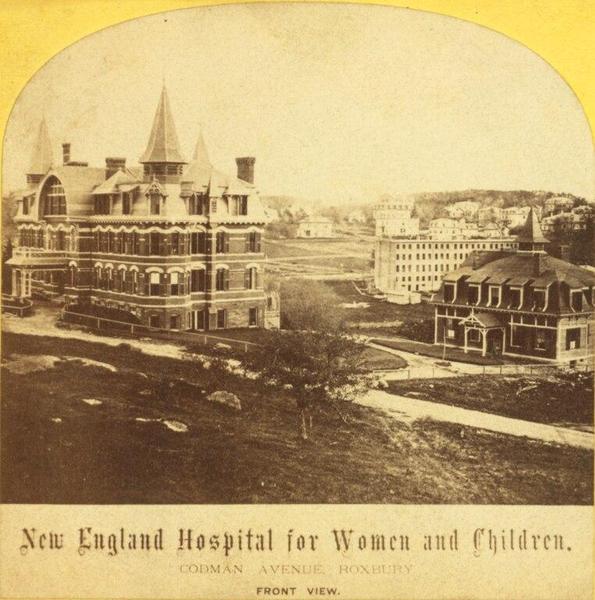

One of only two known photographs of Mary Seacole (1805-1881), c.1873 by Maull & Company in London, public domain. Nurses and their training in America vaulted to the fore in the Civil War, though formal education didn't get underway for another decade. The New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston, Massachusetts, founded in 1872, became the first hospital nursing school in the United States and that's where Mary Eliza Mahoney would shortly get in on the bottom floor of the new profession. The first nursing school to specifically train Blacks wasn't founded for two more decades in 1894, at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C, later Howard University Hospital and nursing school. Mary Eliza decided when she was a teenager that she wanted to be a nurse. Her enslaved parents had been freed in North Carolina before the Civil War and moved to Boston for better opportunity. Mary was born

in the spring of 1845. At that time the African American community in Boston was small, less than one percent of the population and faced discrimination and prejudice.

Still, in 1855, the Massachusetts legislature outlawed segregation in public schools. Mary Eliza started school at the age of 10, going to one of the first integrated

public schools in America. She attended the Phillips Street School in Boston from the first grade through the fourth grade.

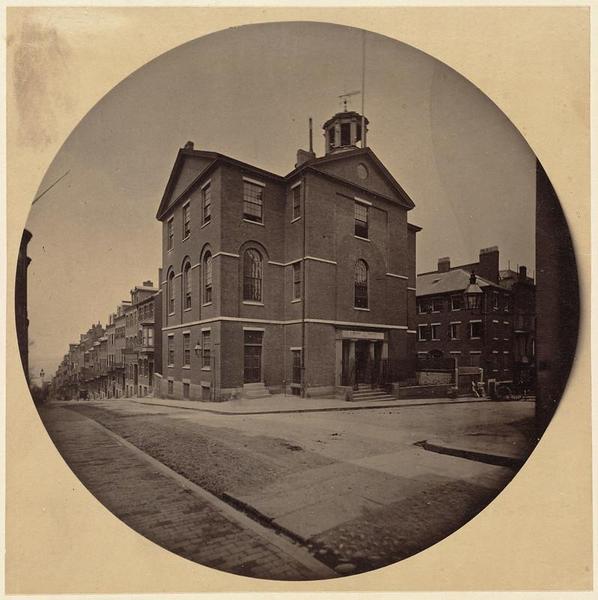

Phillips School, one of the first schools in Boston to become integrated in

1855, Boston Public Library, Print Department

At fourteen, her sights set on being a nurse, the industrious girl got a job at a revolutionary hospital nearby in Roxbury. New England Hospital for Women and Children had been founded specifically to promote women's health and unlike other

hospitals in the North or South, it welcomed both Black and white patients. Though, male patients weren't accepted at the until 1951. At the New England Hospital, all the doctors and staff were women and obstetric care was available to all who needed it, regardless of race or ability to pay. The hospital’s Annual Report from 1867 noted that some of the mothers who gave birth there had been formerly enslaved. Moreover, the hospital was dedicated to helping women study medicine. Mary Eliza worked as a maid, cooked and did laundry, all arduous labor for a woman of her tiny size. Most importantly, she occasionally filled in as a nurse’s assistant. Mary saw the

hospital develop and begin to offer training based on Florence Nightingale’s modern principles of nursing in 1872. She had her toe in the door of the first nursing school in America.

New England Hospital for Woman and Children New York Public Library digital collection, public domain. Five more years would pass before, Mary Eliza Mahoney was accepted to the program. It was 1878 and at age 33, she'd been working at the New England hospital for 15 years. Her acceptance paperwork stated Mary had“suitable requirements and character” for the nursing program. She also had a reputation for tenacity and hard work and that would be important for to graduate from the rigorous program. The 42 students in her class worked 16-hour days on the hospital wards or treating private patients at home while they also

went to lectures and studied. At the end of the 16-month nurses' training, Mary Eliza was one of only four students to complete the course requirements. Awarded her

diploma in 1879, she became the first Black professional nurse in America. Mary Eliza faced overwhelming discrimination in public nursing and decided to focus her

career on private nursing for individual clients. Those who could afford to hire a nurse for care at home were mostly wealthy white families. Maybe there was a silver lining. After decades of long hours and strenuous physical labor, her duties were probably less taxing caring for one patient at a time. She gained a reputation for skill and professionalism, efficient work, patience and kindness. In demand up and down the east coast, she refused to be treated as a servant. Very unusual at the time, she ate at the dinner table with her white patients and their families. Mary Eliza could have been content, but she saw the disparities between white and black nurses and she couldn't sit by. As one of the few black members of the fledgling American Nurses Association, she saw the need for advocacy and support for women

of her race and founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN)

The first convention of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, Boston,

1909 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. The NACGN mission included efforts

"to advance the standards and best interests of trained nurses, to break down discrimination in the nursing profession, and to develop leadership within the ranks of black nurses." At the group's first convention in 1909, Mary Eliza rallied members to work together to increase nursing education opportunity for African-Americans. Mainly due to her efforts, the number of Black nurses doubled from 1910 to 1930. A former professor of nursing Columbia University, wrote of Mahoney in 1954: “This nurse was an outstanding student of her time, an expert and tender practitioner, an exemplary citizen, and an untiring worker in both local and national organizations. "She was a sound builder for the future, a builder of foundations on which others to follow may safely depend." Mary Eliza Mahoney retired after a 30-year nursing career during which she made a personal impression on her clients and their families as well as a larger impact in the nursing field. Again, her leadership didn't stop

there. When Tennessee ratified the women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Mary was among the first women who registered to vote, which she did in Boston's

13th Ward on that very same day, August 18, 1920.

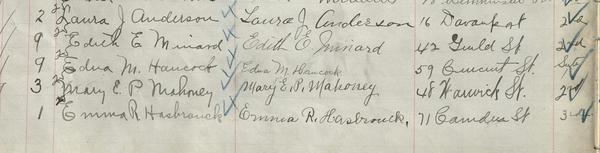

Page including Mary Eliza Mahoney’s voter registration and signature, August 18, 1920, Boston City Archives Her voter registration shows she listed her her occupation as: “trained nurse.” From our vantage, she could have claimed "trailblazing Black

woman who fought prejudice and promoted social change."

After retiring from bedside nursing, Mary took on direction of the Howard Orphanage Asylum for black children in New York City. When she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1922, Mary went for treatment

at the New England Hospital where she had worked many years and received her nurses training. She died there on January 4, 1926 at age 80. Mary Eliza Mahoney's legacy remains as vital today as it was a century ago, with commitment, care and courage, she fostered diversity, equity and inclusion in health care.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

As I write this, it's May Day, also International Workers Day and I want to put in a plug for my book Fannie Never Flinched. Never did I imagine the story would be so relevant. Labor Organizer Fannie Sellins lived during the Gilded Age of American Industrialization, when the Carnegies and Morgans wore jewels, and their laborers wore rags. When millionaires and their corporations got richer and the people went with out the basics, like decent health care and education, social security and workplace health and safety protections. When coal, steel and copper companies extracted our natural resources with no regard for clean air, water or a sustainable environment. Sound familiar?

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|