May 9, 2025 Hello , That meant I had done my research well. But, no, nurses are amazing people on so many levels that I could never achieve. This is National Nurses Week celebrating everyone in the profession and all the essential work they do in every corner of the world. One trailblazing nurse from Australia's outback did not get the respect she deserved. They

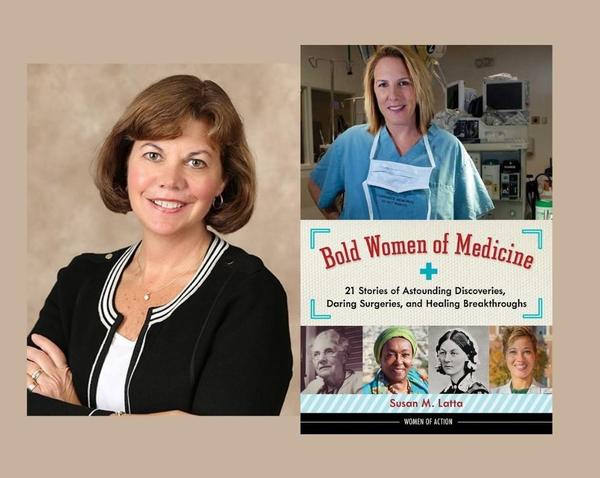

called her a quack. Her story takes us back to the frightening days before the polio vaccine when the threat of paralysis and death spread across America. NPR reported last month, the disease, nearly wiped out, might be poised for a comeback due to the Republican cuts to USAID. More on that below. But first, Author Susan Latta, who wrote the book about Outback Nurse Elizabeth Kenny and how doctors belittled her treatment for polio.

How One Tough Woman Fought Polio from the Outback to Minnesota

Susan wrote Bold Women of Medicine, including the story of

Elizabeth Kenny. When the book came out, she agreed to guest post here and tell us the story behind the story. Welcome, Susan!

No one knows whether Elizabeth Kenny had any formal medical training or learned on-the-job, but that didn’t stop

her.

She had a red cape and nurse’s jumper made and traveled through Australia’s wild bush land to serve anyone who needed help.

Born in Australia in 1880, at a time when girls were not to be brassy, stubborn, or opinionated. Elizabeth had no

intention of following those rules.

I first heard about Elizabeth Kenny when my father had a stroke and was transferred to the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in Minneapolis for recovery. Prior to that, I knew of her in name only.

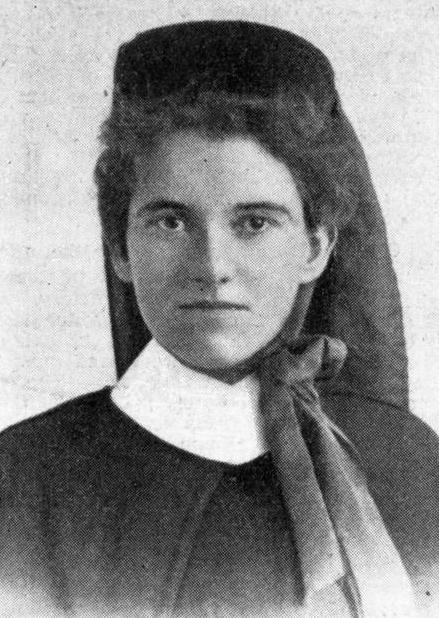

Nurse Elizabeth Kenny, circa 1915, Wikipedia Commons. I remember standing in a long line in the school gym waiting to receive my vaccination in the early 1960s. I had no idea how many people suffered after being stricken by polio.

Decades earlier Elizabeth Kenny had become famous for her treatment for polio, a dreadful

virus that caused paralysis and death. Elizabeth didn’t know it at the time but she discovered her polio treatment one day in 1911 when a frantic farmer called for help

for his two-year-old daughter. Amy's arms and legs were twisted tight with unbearable pain.

Elizabeth Kenny galloped away to send a telegram to her trusted doctor, Aeneas McDonnell. When he replied that it was polio, he said there was nothing to be done. “[Do] the best with symptoms presenting themselves.”

"I knew the relaxing power of heat," Elizabeth said. "I filled a frying pan with salt, placed it over the fire, then poured it into a bag and applied it to the leg that was giving the most pain. After an anxious wait, I saw no relief following the

application. I then prepared a linseed meal poultice, but the weight of this seemed only to increase the pain.

"At last I tore a blanket made from soft Australian wool into suitable strips and wrung them out in boiling water. These I wrapped gently about the poor tortured muscles. The whimpering of the

child ceased almost immediately, and after a few more applications her eyes closed slowly and she fell asleep.”

Amy recovered. But men in the medical field refused to accept Elizabeth's methods. In 1914, Elizabeth Kenny traveled to England to serve in WWI. The Australian Army Nursing Service gave her the title of “sister,” which had nothing to do with religion, instead meaning “senior nurse.” She became known as Sister Kenny.

After the war, she presented her methods to

control the muscle spasms and re-educate the paralyzed limbs to packed rooms of medical men in Australia. Over and over they called her a quack nurse from the bush, and finally she had had enough. She sailed to America to prove her treatment.

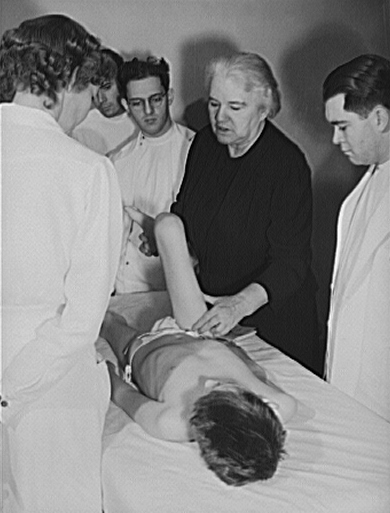

Elisabeth Kenny demonstrating polio treatment to doctors and nurses at the Elizabeth Kenny Institute in

Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1943, Library of Congress.

After being turned away by doctors in New York and Chicago, she landed in Minnesota where a few doctors said her treatment did work.

As word spread she gained nationwide support, even landing on a list of most admired women in America nine years running. The Elizabeth Kenny Institute opened in 1942, and still exists today as Courage Kenny, a facility for stroke and accident victims. Polio was eradicated in America when Albert Sabin’s live polio virus vaccine guaranteed immunity in 1952, just a few short years after Sister Kenny died. Thank you, Susan! In April, NPR reported that despite vaccination campaigns and global aid, Pakistan and Afghanistan have so far been unable to stop transmission of polio. In 2024, Pakistan's numbers spiked to 74 while Afghanistan saw 24 recorded cases.

Child receiving polio vaccine, Republic of Tajikistan, photo by Bryn Sakagawa, USAID.

When Marco Rubio announced the Republican administration had canceled 83% of USAID contracts in March, the press obtained a series of memos drafted by global health officials at USAID estimating how many people would possibly become sick and die if the pause in U.S. aid continued. Among the projections, in the first year, an additional 200,000 cases of polio that cause paralysis and hundreds of millions of infections overall. Some aid has been since restored, specifically the World Food Programme, but no word on polio vaccine programs. This news on polio came from NPR. Then a week ago President

Donald Trump signed an executive order aiming to slash public subsidies to NPR.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources https://www.susanlatta.com/books/bk_bold_women_of_medicine.html

In connection with National Nurses Week: Here's a book I read recently where the main character was a nurse recovering from the strain, mentally and physically, she suffered

working through the pandemic. The book is fiction, a wilderness suspense story about a hiker who goes missing on the Appalachian Trail.

I wouldn't say "you have to read Heartwood, by Amity Gaige!" But I liked it. It's good. There are several points of view from quite different types of characters and the characterization is well done. Heartwood made me stop and think about how difficult the pandemic was for nurses and other medical professionals and I wondered how

many of them have been able to heal and recover. Of note, the American Nurses Association recently revised he Code of Ethics for Nurses, adding a 10th provision that includes two new items affirming nursing’s role in advancing human and environmental well-being worldwide. One redefined duty as, Self-care and patient care are inseparable—nurses’ well-being directly benefits those they serve.

The second confronts structural oppression now identifying racism as a public health crisis and acknowledging intersectionality in healthcare. The Association states the "Code of Ethics for Nurses is a living, breathing body of work that is exercised and interpreted by nurses every day in all they do." Read more here...

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|