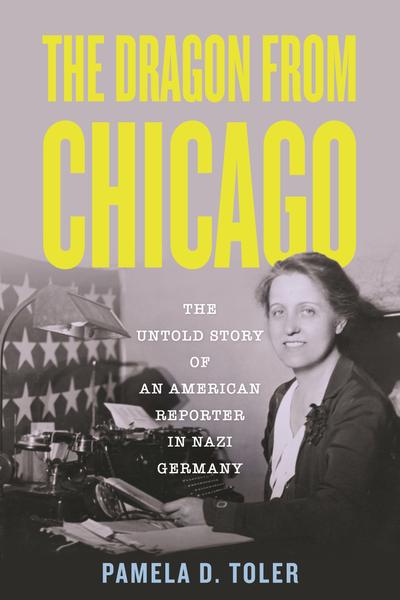

May 16, 2025 Hello , It's not true Americans were in the dark about the rise of Nazi Germany or that they did not know Jewish people were in trouble. One source of information was the intrepid correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, Sigrid Schultz, one of the first European-based American journalists to predict the coming of World War II. "No other American correspondent in Berlin knew so much of what was going on behind the scenes in Germany as did Sigrid Schultz," wrote historian William L. Shirer. She carved herself a place in Adolf Hitler's inner circle from the beginning and despite escalating danger to her life, she took Tribune readers step by step through the rise of Nazi power. Hitler's second in command suspected Sigrid of leaking news reports from the heart of the Third Reich, calling her “that dragon from Chicago,” and tried to engineer her death. Luckily, she survived.

The American Woman Hitler's Henchman Called a Dragon

Sigrid Schultz filed her first dispatches for the Chicago Tribute during the violence of the German Revolution in 1919 at the close of WWI, which I told you about recently in my story

about the courageous leadership of Rosa Luxemburg. Sigrid was a woman in the right place at the right time with the intelligence and drive to take advantage of opportunity when it appeared in a man's world. Born in Chicago, she lived on a quiet street with her immigrant parents, her father from Norway and her mother from German. When

she was eight, in 1901, her father, an artist, obtained a commission to paint a portrait of the king and queen of Württemberg in Germany, and off they sailed to Europe. And yes, they took the family's beloved dog, Barry.

Sigrid Schultz as a child, image courtesy of Jimmy Nuter and WTTW News. The Schultz's settled in Paris and Sigrid grew up traveling with her father, becoming comfortable with his wealthy clients and at ease in elite society. She

graduated from the Sorbonne in 1914 before the family moved to Berlin where she studied history and international Law at Berlin University. The outbreak of WWI split

the family as Sigrid's father was stranded in Munich and she and her mother, a naturalized US citizen, became “enemy aliens” having to report daily to the German authorities. Sigrid supported her and her mother through the lean war years by tutoring English language students. Fluent in German, French and English Sigrid was on the spot several years later when the Chicago Tribune needed an interpreter in Berlin. A quick student, Sigrid soon became a foreign correspondent for the newspaper and in 1925 was promoted to bureau chief in Berlin and the next year chief for Central Europe. She was the first woman to hold such a high position in a major US news organization.

Sigrid Schultz pauses to look at the camera while talking on the telephone. Wisconsin Historical Society Sigrid Schultz witnessed the rise of fascism in Germany day by day, learned of the opening of the first concentration camp, Dachau, heard the shattering glass on Kristallnacht in 1933 when paramilitary forces, Hitler Youth and civilians destroyed Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues. Typed out the news of 30,000 Jewish citizens had been were arrested and sent to concentration camps. On New Year's Day in 1935, members of the National Socialist Party broke out in boisterous celebration in the Black Forest, firings shots in the air jubilant at their leader Adolf

Hitler ascending in popularity and power. Sigrid saw it all and reported by telegram: “…year

two of Hitler’s Fuehrer Germany finds Germany comparable to a mass of cooling lava after a volcano eruption with some people getting burned and nobody certain where the lava will finally settle…” Earlier, Sigrid had anticipated how important the Nazis would become. Her office near the Reichstag gave her close proximity to power and in 1930, her assistant, who later became a Nazi, introduced her to Hermann Göring, who would become Hitler’s second in command.

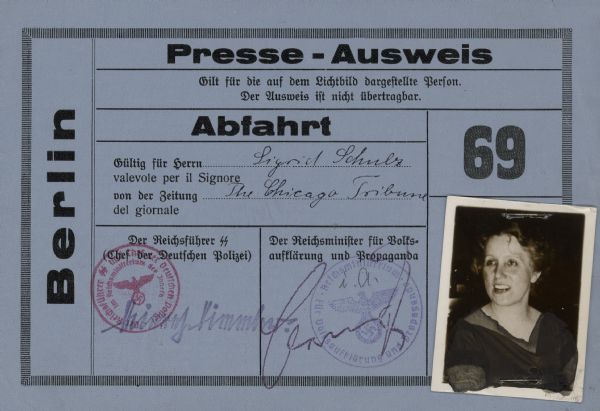

A press pass for Sigrid Schultz in Berlin with a photograph of her attached. Handwritten on the

document is her signature, and The Chicago Tribune. Wisconsin Historical Society. Having paid her dues for years in Berlin as a journalist and making connections with Germany's political leaders, she also brought to bear her training as a chef. Sigrid hosted dinner parties; her gracious manner disarming sources for her news dispatches. Through Göring, she briefly met Hitler, “[He] grabbed my hand in both of his hands and tried to look soulfully into my eyes, which made me shudder, and Hitler sensed it.” In 1932, Schultz interviewed Hitler and grew more alarmed by his his plans. Adolf Hitler told her, "You cannot understand the Nazi movement, because you think with your head and not with your heart."

Sigrid Schultz, US Ambassador William Dodd and Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels seen together at the foreign press ball. Wisconsin Historical Society photo. As she saw more evidence of Hitler's concentration camps and the increasing persecution of Germany's Jews her position became precarious. With storm clouds of war on the horizon, in 1938 Sigrid sent her mother and family dog back to the united States. That year she also began transmitting radio broadcasts for the Mutual

Broadcasting System. After other Allied journalists were expelled from Germany, Sigrid began writing under the pseudonym to protect

her connections inside the the high ranks of Nazi Germany. “John Dickson” filed stories from various European cites, usually Oslo or Copenhagen, with false

datelines. In one story, Dickson reported Germany was prepared for war and predicted the Munich Agreement that allowed Germans to march into Czechoslovakia.

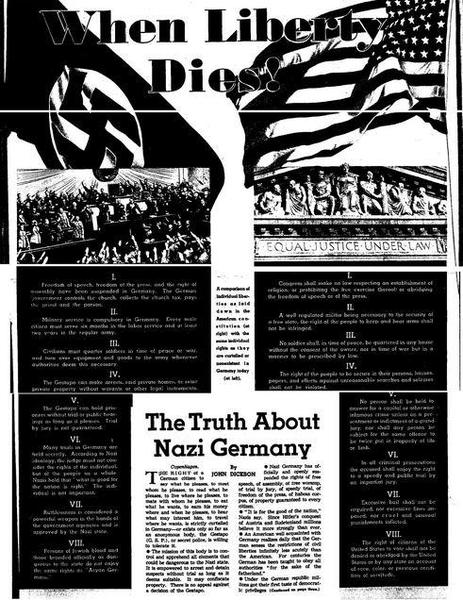

Article featured in The Chicago Tribune

Magazine, by line John Dickson. Image courtesy Westport Museum for History and Culture. In the years leading up to WWII, Schultz and "Dickson" filed more than 1,500 reports for The Chicago Tribune, but in 1941, Sigrid was forced to leave Berlin, not by the Nazi's but the British Royal Airforce. She was setting up to broadcast live for the Mutual radio

network as the RAF bombed Berlin for the first time and was hit by shrapnel and injured. Back in the US, Sigrid toured the East coast talking about her

experiences in Germany, then tried to return to Germany and get back to her job. Nazi officials denied her visa and press credentials and she wasn't able to return until the summer of 1944 after the D-Day invasion. She traveled with US forces through France and Belgium on the road back to Berlin.

When US forces liberated Buchenwald Concentration Camp in April 1945, Sigrid was one of the first journalists to arrive on the scene with Edward Murrow and Margaret Bourke White. This was just three weeks before the liberation of Dachau, reported by journalist Lee Miller April 30, 1945.

I told you Lee's incredible story here last year when the movie came out.

Sigrid recounted how she met prisoners at Buchenwald who despite being liberated would not survive.

“This Frenchman told me: “If you

have the courage, there is a hospital in the back there and there are mostly Frenchmen in there and a few Poles and they are dying. Your American Doctors… I will not be able to save them. It would be good if they heard somebody speak French to them and tell them that they are free, especially your woman’s voice…one man sat up…and said “Is it really true?” And I said “It’s really true, you are free” and he was gone.”

After the war

September 1945, Sigrid Schultz was one of the reporters admitted to the Lunenberg trials of 45 Nazi Concentration Camp officials–men and women–at Bergen-Belsen. She witnessed leading Nazis brazenly lie and feign shock at their accusations. Thirty of the accused were found guilty, of these, twelve were sentenced to death and hanged. Nineteen received various terms of imprisonment. Sigrid Schultz's Germany Will Try It Again, based on her first-hand witness reports describes what she saw as a German-Austrian Military-Industrial Complex composed of wealthy landowners, bankers, and corporate businessmen working for

decades to gain power in Germany, and finally succeeding with a charismatic leader, Adolf Hitler with his many followers and their hysterical adulation. Hmm. Sound familiar? In her final years, Sigrid was working on a history of antisemitism in Germany, as well as a memoir.

Like Catherine Leroy, who never quite moved on after her experiences of the Vietnam War, Sigrid appeared to be forever marked by the horrors

she witness so closely. She died at 87 in 1980.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources https://mosseprogram.wisc.edu/2020/03/04/milne/

As the national news continues to unfold, I strive for a bit of joy. This week I'm loving my lilacs. Wish you could get a whiff. They're wonderful to look at and to smell.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|