By some counts the crowds of mostly women demanding a 20-percent decrease

in meat prices in Hamtramck, Michigan, swelled to 7000 people by the end of July 1935.

Unfortunately, the meat boycotts of 1935 did not achieve the twenty-percent price cut the women demanded, but it was clearly a turning point for women's engagement in

politics.

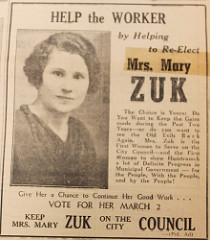

Feisty Mary Zuk had left at job the local Dodge factory to raise her two children in the tight-knit Polish community near Detroit before getting elected to

lead the boycott. She ended up leading a racially-integrated delegation to Washington, DC to meet with Secretary Wallace, which triggered an investigation into meat prices. Later, she ran for a seat on her local city council and won.

In the 1940s and 50s housewives again rose up to demand affordable meat prices. They also organized to demand sanitary storage, packaging and display of foods, such as loaves of bread, which might be handled by a number of shoppers before being selected for purchase.

Then came the mostly forgotten "housewives’ revolt" of 1966. It began in Phoenix, where homemakers, fed up with bread prices, boycotted bakeries and baked their own. But the real flashpoint came in Denver.

That where 52-year-old grandmother Mrs. Paul West (as newspapers identified women then) noticed olive prices had quadrupled in a month. A store official told her to “stick to your cooking.” Wrong move. West quickly organized boycotts of five supermarket

chains—about 150 stores in total. The result: prices dropped by up to 20%.

Meanwhile the movement expanded to other cities across the U.S. and Canada.

“Mad Housewives Spread Boycott” read a headline in Lowell, Mass.

In Dallas, women organized what they called a “ladycott” of local supermarkets. In Buffalo, a group called Women on the Warpath boycotted eggs. And the We’ve Had It Club in

suburban Atlanta formed a motorcade, taking its protests from store to store.

Then came housewives Lynn Heidt, Jackie Kendall and Bonnie Wilson tagged "Code Breakers" for their work educating shoppers on food expiration dates.

They protested at grocery stores, told their story on national radio and TV and went straight to the top of the National Tea Grocery Chain where Lynn Heidt had purchased the sour milk. The women bought a share in National Tea and went to a

shareholders meeting where they shout questions at the company's president.

National Tea responded by hiring a major law firm to investigate, or “spy” on the women and

even called the husbands of two of them to ask why “they could not control their wives.”

Thousands of American women who’d never been involved in a protest before—many

of whom said they’d had to ask their husbands’ permission to participate in the supermarket boycotts—now had experience on the front lines and pantry politics gave way to the rise of the Women's Movement in the 1970s and increased opportunity for women.

The backlash came immediately and only appeared to let up in succeeding generations. Today the conservative, anti-labor, anti-immigrant, anti-women politicians are back with a vengeance, pushing an agenda that favors billionaires and deepens women's struggle to feed their families and balance their budgets.

How will we women of today continue the fearless and creative fight for what our children and grandchildren deserve?

Email me. Let me know what you're thinking.