May 30, 2025 Hello , I lost a week somewhere in May. Or maybe it was just that Memorial Day came early this year. Anyway my feature story on what was originally called Decoration Day comes in the wake of the three day weekend. The holiday has changed over the decades, taken on different meanings for different people, who celebrate in different ways, from department store sales and the beginning of summer camping

trips to attending events to remember our war dead or visiting family graves. It's been that way from the beginning. At the end of the Civil War, the nation reeling with grief, people in hundreds of towns set aside a day to decorate the graves of the fallen soldiers. Though some hoped it would unite the country, the days has almost

always meant different things to different people. Americans celebrated the first Decoration Day May 1, 1865 to honor men dubbed "Martyrs of the Race Course." It quickly faded from common memory for nearly 150 years, only recently coming to light in a history archive at Harvard.

Martyrs of the Race Course

May 30, 1868 is known as the first official "Memorial Day" in the US. Dignitaries gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to honor Union soldiers who died

during the Civil War. General John Alexander Logan, a Union veteran designated the day for “strewing with flowers or

otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

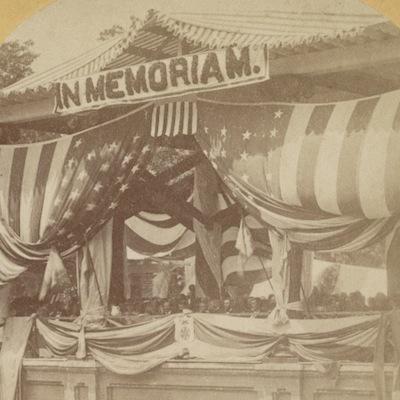

Celebration of the first official Decoration Day at Arlington Cemetery, May 30, 1868. President Grant and General John Logan seated at flag-draped reviewing stand. Photographer by John F. Jarvis, Library of Congress. Then in 1996, a history

professor discovered a handwritten soldier’s account of a similar event taking place in South Carolina the waning days of the Civil War. This document penned by an eyewitness led the researcher to find a newspaper report from the Charleston Daily Chronicle more fully describing how ten thousand formerly enslaved people

gathered in the ruins of Charleston, South Carolina, to decorate the graves of union soldiers.

Charleston, S.C. View of Ruined Buildings through Porch of the Circular Church], April 1865.

Library of Congress, George Barnard, photographer. The once beautiful port city, birthplace of the Confederacy had

finally fallen after nearly two years of siege and heavy artillery fire by Union forces. Confederates abandoned the city in bitter defeat on the 4th anniversary of Jefferson Davis’ inauguration (Feb. 18, 1861). They left behind a mass grave of quickly buried Union prisoners-of-war at Charleston's Washington Race Course and Jockey Club. The track where Southern gentility had once viewed the steeplechase became an outdoor prison in the final year of the war. At least 257 Union captives perished there and were dumped in a grave behind the grandstand where officers had been imprisoned. When Federal troops marched into the city, nearly all white citizens had fled and the former enslaved residents wasted no time making plans to honor those who'd made the ultimate sacrifice made for their freedom. A group of men got to work exhuming each body from the mass grave and reburying the soldiers with dignity, creating individual graves and building a fence around the site and declaring them Martyrs of the Race

Course.

The club house and stands for the Washington Race Track where union officers were

held had been designed by Charles F. Reichardt in the 1830s. Library of Congress

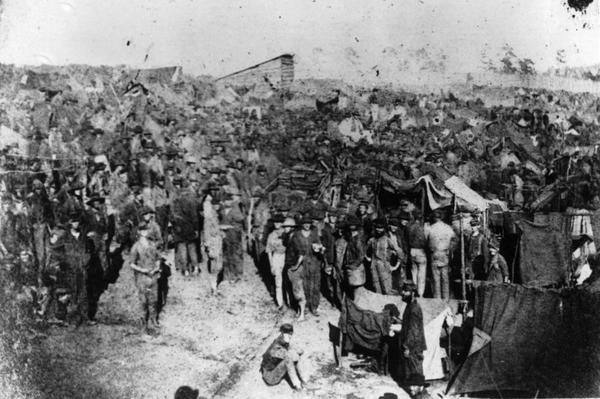

The prisoners at the Charleston Race Course Prison had come for the infamous Confederate prison in Andersonville, Georgia. In 14-months,

Andersonville had held 45,000 Union soldiers, nearly 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, starvation, overcrowding, and exposure. The only known photographs of the prison during its operation were taken by photographer AJ Riddle in August 1864.

Taken from a guard tower near the north gate along the west wall, this photograph shows

the ration wagon with prisoners crowded around. The structure at upper center is the Sutler's shanty. After the war, Captain Henry Wirz, in charge of the prison, was tried and executed for war crimes and the deaths of 13,000 American soldiers. Andersonville Prison,

August 1864. National Park Service, public domain. As General Sherman's forces marched toward Andersonville in the late summer of 1864, Confederates relocated

thousands of captives, fearing they would be liberated. Hundreds were sent to Charleston's prison at the race course. Conditions were not much better. The prisoners got little food or shelter. Smallpox and yellow fever, spread rapidly through their ranks. Those who died were remembered in the first known Decoration Day, May 1, 1865. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

Graves of Union soldiers were buried behind the Charleston's old racetrack's stands near the present

intersection of Tenth Avenue and Mary Murray Drive. Library of Congress

Of the ten-thousand gathered, some 2,800 were school children according to the Charleston Daily, who marched over the burial ground singing John Brown's Body and leaving flowers on the graves. Later they honored the dead singing The Star-Spangled Banner, America and Rally Round the Flag. Adults took their turn adding flowers to the graves, each marked with a headstone, though no names could be carved upon them, for they were all unknown soldiers.

When the ceremony finished, the crowd retreated to the infield and the day unfolded as as Memorial Day does for many of us today. They enjoyed

picnics and good company, listened to speeches and watched soldiers drill. A full brigade of Union infantrymen participated, including the 34th and 104th United States Colored Troops, who marched in a double column around the burial ground.

Members of Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, Washington, D.C., c. 1863, Photographer William Morris Smith, Library of Congress.

This first Memorial Day in South Carolina was held to honor those who fought for justice and liberation. But later in the South, Memorial Day speakers

often focused on Christian ideals of noble sacrifice. Memorial Day rhetoric bolstered the Lost Cause tradition in honoring the Confederate dead as the true “patriots,” defenders of their homeland, sovereign rights, and a natural racial order based on white supremacy,

Today's apolitical Memorial Day and the on

which people must "'remember the sacrifice' of U.S. service members, without critically reflecting on the wars themselves, did not emerge by accident," observes writer Cass Teague in the Nashville Pride Newspaper (5/25/2023).

"It came about in the Jim Crow period as the Northern and Southern ruling classes sought to reunite the country around apolitical mourning, which required erasing the “divisive” issues of slavery and Black citizenship. These issues had been at the heart of the struggles of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Today, the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club survives only as an oval in what is now Hampton Park, named for Wade Hampton, a Confederate general who became the avowed white

supremacist Governor of South Carolina after Reconstruction. The graves of the Martyrs of the Race Course are gone too; their remains were reburied in the 1880s at a

national cemetery in Beaufort, S.C. Historian David Blight who discovered the evidence of the nation's first Memorial Day says of the participants, “by their labor, their words, their songs and their solemn parade created for themselves, and for us the Independence Day of the Second American Revolution.”

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources https://backstoryradio.org/shows/grave-matters/

Two months ago I wrote about how sources of information I used to research the women in my book Pure Grit about US army nurses in WWII had disappeared from the US Naval Heritage Command website after President Trump's executive order "Ending Radical Government DEI Programs."

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|