January 9, 2026 Hello , They called Geraldine "Jerrie" Monk "the flying housewife," in the mid-1960's, which sounds about as silly as The Flying Nun, a fantasy TV series in the same time period staring Sally Field. Jerrie Monk did what the much-more-famous Amelia Earhart failed to do—because she was a "bored housewife." Born in 1925, Jerrie broke ground in the sky for women. She was the first female licensed by Ohio to manage an airport, Price Field in Columbus, OH. The first woman pilot to fly from the United States to Africa over the North Atlantic and first female to land a plane in Saudi Arabia, causing some wide-eyes at the airport. Saudi women weren't even allowed to drive cars until 2017. Jerrie set flying speed and distance records for her size aircraft—21 records in total. She flew planes for adventure and love of travel in an era when most middle class American women were homemakers. But Jerrie Monk did not become the first woman to fly around the world without facing a few skeptical onlookers and harrowing

moments.

Flying Housewife Who Set World Record... in Heels 👠

Jerrie's flight around the globe required permission to land and take off from many different airports, the administrative and logistical steps sometimes more difficult and time

consuming than piloting the airplane. Jerrie knew someone had make a mistake when she landed her flight from Tripoli and in Cairo. As soon as the wheels of her 1953 Cessna 180 touched down, three military trucks careened from another taxiway, screaming toward her. The

vehicles screeched to a stop just a hand-length from her plane's nose, and soldiers jumped from the trucks, aiming their guns at her. She'd missed the Cairo airport and accidentally landed at a secret Egyptian military base! When Jerrie took off her helmet and the

soldiers saw she was a woman, they held their fire. But they didn't immediately get over their shock at seeing the 38-year-old mother of three climb down from the cockpit in heels.

Jerrie

got her first ride in an airplane when she was 7-years-old. After fifteen minutes in the sky, she announced that when she grew up, she would fly around the world. “I was stuck in a little town called Newark, where no one went anywhere,” she later recalled. “I also grew up in an age where there was no television and you could only learn about the world from geography books. I had no idea what it was like in other parts of the world but I wanted to be different than everyone else and find out.” . Right away, gender-stereotypes raised their ugly heads. Her school assigned boys to mechanics class and sent her to learn embroidery, which she refused to do. In middle school she heard about the Ohio Women’s Protective Laws that imposed work restrictions on women. These included maximum working hours, bans on night work, seating requirements, weight-lifting limits, and minimum wage provisions. Meant to protect women, the laws

kept them from advancing and earning equal pay to men. “I was never going to abide by man-made laws that said women couldn’t do

something.”

“Nobody was going to tell me I couldn't do it because I was a woman,” said Mock, who wore a skirt and

blouse on her around-the-world flight, putting on high heels when disembarking at stops. Starting college in 1943, Jerrie became Ohio State

University's only female aeronautical engineering student. Though she wanted to be a pilot, Jerrie married a pilot, left school and became a housewife, a common path women took in the 1940s. She and her husband Russell Monk had three children. But she did not give up her desire to fly. After beginning lessons in 1956, she quickly proved to be a natural pilot, soloing after less than ten hours of instruction. Two years later she earned her license, using landmarks for navigation rather than relying on radios. “I plotted more complicated routes to fly than experienced pilots,” she recalled. “Even the old-timers asked me how I navigated.” Not only could Jerrie handle airplanes, in 1961, she managed Price Field in Columbus, responsible for fueling airplanes and tying them down, “The male instructors did not like a woman telling them what to do,” Mock

recalled. “I did not worry about it and ignored them.” But part of her job a the airport was making coffee. She didn't like that and she told her husband she was bored with her duties at home and wanted adventure. Maybe you should fly around the world, he joked. Thought he wasn't serious, Jerrie jumped at the idea. As a child, she'd heard about Amelia Earhart and when she discovered no women pilot had yet completed a trip around the world, she started plotting a

route.

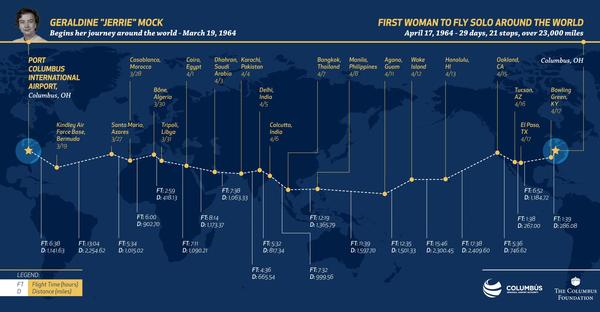

Jerrie with her children Roger, Gary and Valerie, 1964. To get permission to travel through foreign airspace, Jerrie went to Washington D.C. and visited embassies for the 21 countries where she planned to stop over. For official records, she arranged for observers and timers to document all her takeoffs and landings. The Columbus Dispatch help fund Jerrie's trip and she brought a typewriter on the adventure to write letters and articles for the newspaper. On March 19, 1964, Jerrie boarded her red-and-white single-engine Cessna called Spirit of Columbus and started

the engine. “The tiny plane raced down the runway and literally leaped into the air, eager to explore the world,” Jerrie

recalled in her memoir, Three-Eight Charlie. “How I loved my beautiful plane!” But Jerri had some naysayers. She'd never flown over an ocean before and had only clocked 750 hours flying time. As she lifted into the sky, she heard the tower controller on the radio, “Well, I guess that’s the last we’ll hear from her,” he said. On the 23,000 mile flight she met with only minor mishaps including ice on the wings, sand in the engine and and a burned out antenna motor. “Scared? Let's not use the word scared,” she told a reporter with a laugh. “Airplanes are meant to fly. I was completely confident in my plane; I trusted it completely. I

had plenty of gas, a good engine. You just kind of used your head.”

Jerrie

touched down back home at the Columbus airport on April 17, 1964, 29 days, 11 hours and 59 minutes later. The first woman to pilot an aircraft solo around the world.

Jerrie Mock first women to Solo flight around the world, 1964 Press Photo.

Thousands came out to greet her and newspapers across the country carried her story. “It didn’t seem right that these people should say such wonderful things about me,” she wrote. “I just went out to have fun and to see the world.”

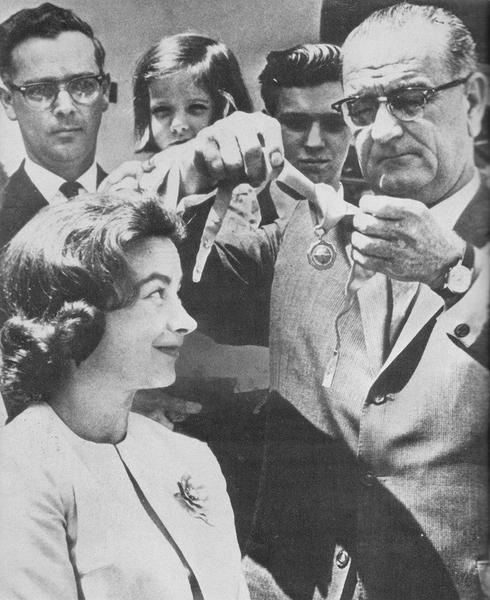

Even so, a few weeks later, she visited Washington D.C. again. This time to get a medal from the president, Lyndon B. Johnson.

President Johnson awards Jerrie Mock the Federal Aviation Agency's Gold Medal for Exceptional Service, May 4, 1964. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian

Institute. Her pioneering flight came 27 years after Amelia Earhart disappeared on her round the world trip in 1937. Jerrie said dozens of women, both in the United States and other countries, were capable pilots and could have accomplished the feat before she did. Makes me wonder how many of the rest of us are walking around with untapped potential, not believing the sky is right there, within our grasp.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at email@MaryCronkFarrell.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|