September 5, 2025 Hello , Marie Sanchez spoke softly, but her message was a clarion call in Geneva at the 1977 United Nations Convention on Indigenous Rights. The US "government is after our coal, our gas, oil and uranium" she said. And forced sterilization of American Indian women is part of the plan to get our

resources. Evidence of forced sterilization at Indian reservations across the country had first come to light in 1972 during the The Trail of Broken Treaties protest and demonstration. During a seven-day occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington DC members of the the American Indian Movement discovered records of

the medical procedures. Marie Sanchez and other Indian women marched, protested, pushed for the truth and conducted their own investigations over the next decade. There's been no apology, no admission of wrongdoing, but the evidence is clear, After the passage of the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970, the

Indian Health Service (IHS), forcibly sterilized as many as 70,000 Native women over just six years, often without their consent or knowledge.

This is What Resilience Looks Like

Marie Sanchez, chief tribal judge for the Northern Cheyenne

Reservation

in Lame Deer, Montana, heard the sterilizations were happening at hospitals on and off reservations. She asked around. Just in conversation with my own cousins and friends in the village in a week's time we found 26," she said. "I thought this was even at that small number alarming because there's only 2300 of us [on the reservation].

Marie Sanchez speaks with WNED, Buffalo, NY, about her investigations into forced sterilization of American Indian women, April 15, 1977. Marie spoke with one woman who saw the IHS doctor complaining of persistent headaches and was told a hysterectomy would cure them. "She did she took his word as almost all and then woman would probably take the word of a Doctor and she had the operation and her headaches came back and they found out later she had a brain tumor." Two 15-year-old girls of the northern Cheyenne tribe went to a Montana hospital with appendicitis. Without their knowledge, or that of their parents, both girls received tubal ligations along with their

appendectomies.

Dr. Connie Pinkerman-Uri, Choctaw/Cherokee, also conducted her own study, finding that 25% of American Indian woman of child-bearing age had been sterilized without their consent that the Indian Health Service had “singled out full-blooded

Indian women for sterilization procedures.” Some Indian woman agreed to sterilizations after being told the procedure could be reversed. Others just took

the advice of the doctor. "I really feel that they did not have a choice," Marie told Jim Lehrer of the MacNeil/Lehrer Report. "Because

in a situation such as a reservation, where poor people have to depend on Indian Health facilities, they generally take the word of a white doctor who says, "This is the best thing for you." And I really feel that there is a heavy element of coercion."

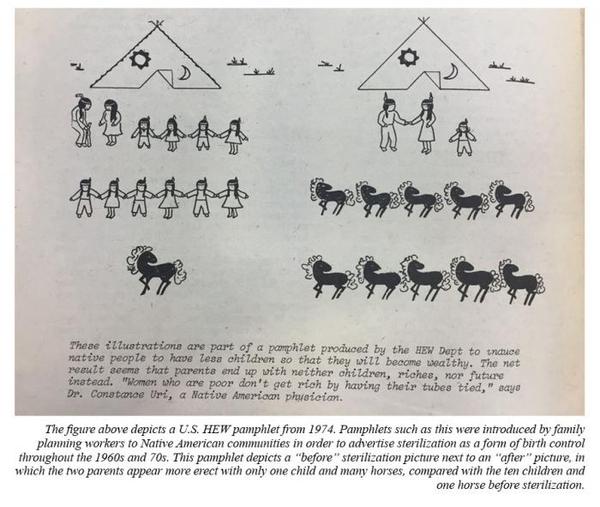

In 1974, the US Department of Health and

Welfare which oversees the IHS published a pamphlet used to convince Native women to choose sterilization to limit their families so they would become wealthier.

Many IHS physicians, mostly white males, believed Native American women were not intelligent enough to use other methods of birth control and so sterilization

was the most reliable birth control method. In addition, the influx of surgical procedures was seen as good training for physicians and as a practice for resident physicians. Politicians wanted to target poor women, the disabled, and the women of color to reduce medicaid and welfare spending. In 1976, Congress'

investigating arm, the Government Accounting Office agreed to investigate Native American sterilization in the IHS. Marie Sanchez claimed the report sought to discredit her and Dr.Uri. The GEO study found that between 1973 and 1976, four of the 12 Indian Health Service regions sterilized 3,406 American Indian women. It found that there were consent forms in the medical files, but most of these forms did not comply with IHS requirements. The GEO report but stopped way short of charging that the government was sterilizing Indians against their will. The study did show 36 women under age 21 were sterilized during this period despite a court-ordered moratorium on sterilizations of women younger than 21. A direct effect of sterilization of Native American women was a decrease in birthrate. In 1970, the average birth rate of Native American women was 3.29. By 1980, it had declined to 1.30. Sanchez hoped to motivate women to file lawsuits against the IHS, but with the strong Native cultural focus on family, for them to publicly admit that they had unknowingly given up their reproductive rights would be devastating for them and their relations. "Eleven more discouraging than high legal bills," Marie said, "is the risk of losing one’s place in the Indian community, where sterilization has

particular

religious resonance.”

In Washington State, a class-action suit filed against the government in 1977 on behalf of three Northern Cheyenne women from Montana whose names were kept private. The suit alleged the women were sterilized without their full consent or knowledge of the surgical procedure and its ramifications. The suit never went to trial, as lawyers for the government offered each of the three women a cash settlement on the condition that the terms of the agreement would

remain sealed, along with their names. The women’s attorney believed the settlements were meant to avoid publicity that might encourage other victims to sue.

Marie

sought justice on the world stage. She addressed the United Nations Convention on Indigenous Rights in Geneva declaring the sterilization of Indian woman was a tactic of modern genocide and accused multinational corporations of being indirectly responsible by targeting 500 billion tons of coal on Indian land.

For Native

Americans to survive, they must gain back control of their lands, she said, asking the conference to recognize the sovereignty of North and South American Indigenous nations. On the MacNeil/Lerer Report Marie elaborated. "The Indians don`t quite number a million, if sterilization such as

this continued to take place then our gene pool will be very, very small. And I really feel that in the past we`ve suffered different methods of genocide, such as in one instance where we were offered blankets with smallpox to exterminate us; and in this day and age I feel that it`s done [for what is seen as nobler reasons].

By 1980, advocacy by Marie Sanchez, other Native women and other women of color resulted in federal regulations that

offered women some protections from unwanted sterilization procedures. The new regulations required, for example, an extended waiting period—from 72 hours to 30 days—between consent and an operation. on the The Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota developed a policy to have Indian midwives or nurse advocates file reports on hysterectomies, which are subject to committee review every three months. Census figures are showed a steady rise in births from 27,542 in 1975 to 45,871 in 1988. Still, reservation hospitals are consistently underfunded and recently, some hospitals have reduced or eliminated obstetric services, forcing women to drive up to two hours to give birth. These factors directly affect baby and maternal health. Maria Sanchez was a

teacher at Montana State University and Chief Dull Knife College, a human rights activist, Chief Judge of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe and a skilled linguist. As a

woman, she drew her strength from the traditional spiritual people of the Cheyenne nation. She believed for Native Americans to survive, children must be taught the language and traditions of their indigenous nations. To that end, she helped compile the Cheyenne Dictionary. Though soft, her powerful voice lives on.

In more recent news on this topic... A spokeswoman for the National Congress of American Indians Task Force on Violence Against Women spoke out in September 2020, after a whistleblower alleged immigrant women held at the Georgia ICE detention Center were undergoing sterilization without their consent. A congressional investigation in November 2022, found some immigrant women at the Georgia detention center may have had unnecessary and invasive medical procedures, but not a mass number

of hysterectomies. The report did uncover serious problems at the facility with medical care, policies and questionable procedures sometimes done without full consent of the patient.

“I am deeply concerned about the allegations of the whistleblower." said Juana Majel

Dixon. "As one of the thousands of American Indian women sterilized without my informed consent, I know the consequences of such federal policies for women and Indian Nations. Forced sterilization was the means used to terminate Indigenous peoples. It failed, our Nations survive, but we will never forget.

Like my article today? Forward this email to family and friends.

When history comes full circle...

Downtown Los Angeles 1937, courtesy UCLA Library.

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|