September 12, 2025 Hello , They're known as the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. For nearly 50-years, the women have been searching for their grandchildren stolen and illegally adopted in the late-1970s under Argentina's fascist dictatorship. After a military coup in Argentina in 1976, Lieutenant General Jorge Rafaél Videlan's government set out to destroy all resistance. Armed men in masks, death squads, showed up in

neighborhoods, shooting suspected communist guerrillas and left-wing sympathizers and abducting men, women and children. Some 30,000 Argentine people disappeared in the years

1976-1983 while the military dictatorship held power. Students, trade unionists, writers, journalists, artists, basically any people believed to be a threat to the government were taken to detention centers scattered across South America. The Argentinian government denied all allegations of killing and kidnapping while ordering mass executions. Unknown numbers of people were thrown from airplanes into the sea, died in captivity or were tortured to death. Beneath the violence lay a systematic scheme to steal babies and children, some born in clandestine maternity hospitals, and adopt them out to families who supported the regime. This past week one of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo died at age 106. Rosa Tarlovsky de Roisinblit lived to see some justice for her daughter's killing and the disappearance of 500 Argentinian children.

The Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo Search for their Stolen Grandchildren

Rosa

Tarlovsky de Roisinblit became a founding member of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo Association after her daughter Patricia, son-in-law José Manuel Pérez Rojo and their one year old daughter Mariana disappeared. They were kidnapped in 1978 by a task force of the Argentine Air Force. Rosa's granddaughter Mariana was returned to José Manuel's family, but she never saw her daughter or son-in-law again.

Grandmother de Plaza de Mayo Rosa Tarlovsky de Roisinblit in

2016. Rosa's daughter Patricia was eight months pregnant at the time of her kidnapping. While held in a

clandestine detention center,she gave birth to a baby boy who was taken from her and give to a family connect with the Air Force. The government placed a high value on

the children who would shape the future of Argentina. Military families on a waiting list to adopt the stolen children chose them according to their sex, hair and eye color. Children not meeting their specifications went to orphanages and were adopted later in their lives. Relatives searched everywhere for information about what had happened to their missing family members, checking at courts, police stations, hospitals, churches. They met with silence. The first group to organize against the Argentina regime's human rights violations in 1977, was the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. In public defiance of the laws against protest and mass assembly, they gathered every Thursday at Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires in front of the presidential palace.

Six months later, a mother who was also a grandmother stepped away from the round and asked, "Who is looking for your grandchild, or has your daughter or daughter-in-law pregnant?" At that time, there were twelve women who understood that we had to organize ourselves to look for the children of our children kidnapped by the dictatorship. The following Saturday, October 22, 1977, we met for the first time and began a collective struggle that continues to this day. ~Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo

Little by little, we began to group together to share data and give each other

strength. Less than a month later, December 1977, the regime struck back. Three women of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo movement were abducted and

disappeared.

The Abuelas persisted, marching alongside the Madres and engaging in daring investigations, meticulously searching birth registries for signs of falsified documents and following tips whispered to them by nervous onlookers at their marches.

They leaned into their image as kindly grandmothers as they operated like spies, once smuggling sensitive documents across the border from Brazil by hiding them within chocolate wrappers. Meeting surreptitiously in cafés, they used knitting needles or fake birthday presents to conceal their real purpose, passing documents under the table. When the dictatorship collapsed in 1983, the grandmothers came out in force, pressuring the new government to investigate the disappearances and bring charges against the perpetrators. Geneticists from the United States worked with the Grandmothers to store blood samples from family members and the women started public awareness campaigns in an effort to get the missing grandchildren to contact them. Their work led to the creation of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team and the establishment of the National Bank of Genetic Data. As they identified missing children, the Grandmothers fought through the court systems to annul the unlawful adoptions and returned a number of children to their biological families. By 1998 the identities of about 71 missing children had been documented. After decades of searching, Rosa Roisinblit was reunited with her grandson Guillermo Pérez Rosinblit in April 2000, after an anonymous tip led to genetic testing that confirmed his identity. Other grandmothers have not found their grandchildren. The group now has a website to publicize the missing children who are now in their 40s or 50s. People can click on different options...

Amelia Herrera de Miranda is still looking for her granddaughter Matilde Lanuscou. On September 5, 1976, a neighbor showed her the front page of the Clarín

newspaper: "Look, Amelia, what an outrageous thing happened!" The headline read: "Extremists killed in San Isidro." Amelia discovered her daughter, also named Amelia, was among those who disappeared after the brutal operation by military forces. The entire family, mom, dad, two brothers and six-month-old baby Matilde

disappeared.

Baby Matilde and her mother Amelia Barbara Miranda of San Isidro before their disappearance. Grandmother Amelia and her husband Juan dedicated themselves to searching for Matilde. Every day, Amelia arrived at the Abuelas headquarters hoping for news. She prepared the midday meal for all the Grandmothers. In January 1984, at the urging of Grandmothers, authorities

investigated unidentified remains in the cemetery of Boulogne, Buenos Aires. Five coffins were uncovered and forensic evidence identified Amelia Barbara Miranda, her husband Roberto Francisco Lanuscou, and their two little boys.

"And where there was a tiny little [coffin]," says Grandmother Amelia, "where six-month-old Matilda should have

been, they opened it, unwrapped a green blanket, and there was only a clean teddy bear, a pacifier..." Matilde is still missing. This summer, the Grandmothers announced one more child had been identified, bringing the total to 140 grandchildren found. "Recovering your identity is a beautiful thing," says Juan José Morales. He was nine-months old in May, 1976, when he, his mother, paternal grandparents and three uncles all disappeared.

Juan José Morales kidnapped at nine-months has reunited with his Grandmother. Juan Jose didn't know he was adopted until after his parents died, and his "siblings" broke the news and gave him his original ID card. His maternal grandmother had been searching for him and in 2008, documents and DNA studies confirmed his identity. A number of Army,

Navy, security forces and police forces have been convicted and sentenced to prison for crimes during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship, including homicide, kidnapping, torture and rape. In 2016, Rosa Roisinblit was in court to see Omar Graffigna, Commander of the Air Force at the time of her daughter's disappearance, sentenced to 25 years in prison on charges the abduction and torture of Patricia and her husband.

The civilian Air Force employee who had been given Patricia's baby boy was imprisoned for 12 years. "The pain is still there, this wound never heals... But to say I'm stopping? No, I'll never stop," she said at the time, aged of 97. The vast majority of the men and women who disappeared

without a trace were killed and by the regime, leaving no record of their fate. In 1983, Navy Captain Adolfo Scilingo testified to the National commission on Disappeared People describing how "prisoners were drugged, loaded onto military planes, and thrown, naked and semi-conscious, into the Atlantic Ocean." The US State Department saw Argentina as a bulwark of anti-communism in South America and Henry Kissinger met several times with Argentine Armed Forces leaders after the coup, urging them to destroy their opponents quickly before outcry over human rights abuses grew in the United States. The US Congress approved a request by the Ford Administration, to grant $50,000,000 in security assistance

to the junta. In 1977, the US Department of Defense authorized $700,000 to train 217 Argentine military officers and in 1977 and 1978 the United States sold more than $120,000,000 in spare military parts to Argentina. When Jimmy Carter became president he convinced Congress to cut off all US arms transfers to Argentina due to the government's human rights abuses.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

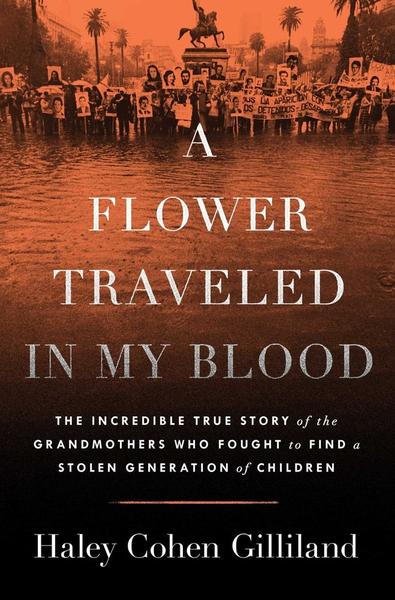

"When I officially began working on this book in 2021, I never could have anticipated how resonant it would feel today." Haley Cohen Gilliand goes on to say, "The unmarked cars and

masked law enforcement officers appearing across the country evoke alarming patterns from Argentina’s past and underscore the importance of protecting civil liberties and upholding due process. "Argentina’s history serves as a stark warning of how a government that puts its agenda over the law can descend into tyranny, while the story of the Abuelas is a powerful reminder of

how, together, ordinary citizens can resist."

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|