2025 Hello , Hey, grab a coffee or your beverage of choice and sit back to read this one! We won't dance in an Oklahoma wild west show and the stages of New York City and Paris. Study at the Sorbonne, escape the the Nazis? Publish a book and have our artwork in the Smithsonian? But we

can ground ourselves in meaningful stories, be curious and courageous, persevere to realize our talent, have grace in joy and sorrow and find home when we need it—all in the life of Mary Alice Nelson "Spotted Elk" Archambuad. It's a shame most of us have never heard of her before. “She was a remarkable person in any light and led, I think, one of the most amazing unknown lives of any modern American women.” That description comes from the former director of the Penobscot Nation Museum on the island Molly called home. In the spotlight on stage the dark-haired dancer twirled, bells tinkling on her ankles and feathers in her hair, as the cheering began and the orchestra drumbeats rose—like thunder from far mountains echoed in chants around bright fires by lakesides, long ago. Suddenly, silence, then applause, bursting like a thundercloud, and cries for an encore.[1] Molly Spotted Elk took stages by storm across two continents in the 1920’s and 30’s dancing for New York City clubbers, Oklahoma cowboys and European commoners and

kings.

Here's How to Live Life Fully

Molly Spotted Elk starred in one of Paramount's last silent films, The Silent Enemy released in 1930. She withstood the cold Canadian forest for more than a year during

filming. Set in pre-colonial times, the movie depicts the Ojibwe tribe enduring famine as a power struggle arises between a skilled hunter and corrupt medicine man. Molly pays “Neewa,” the tribal chief's daughter.

In what was highly unusual for the time, The Silent Enemy featured an all-native cast and authentic costumes, tools, and practices. It was

inspired by a Museum of Natural History expedition and praised for its relative realism and stunning natural scenes of animals.

Photograph from the film, featuring Baluk the hunter (Actor

Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, left) and Chief Chetoga (Actor Chauncy Yellow Robe, center). Woman actress unidentified, unsurprisingly. The

Saturday Evening Post extolled Molly Spotted Elk's performance and stated The Silent Enemy should win a Pulitzer Prize for "best American dramatic creation for the year 1930.” As you might guess, the movie flopped at the box office. That didn't help Molly's film career. Native American women were rare in leading roles at the time. in 1914, Lilian St. Cyr, “Princess Red Wing,” was the first Native American film actress to appear a silent film and performed in more than 70 movies over her 15-year-career—both shorts and Hollywood features. Molly Spotted Elk did appear as an extra in several Hollywood classics, including “Last of the Mohicans” (1936), “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (Warner Bros., 1936), “The Good Earth” (MGM, 1937), and “Lost Horizon” (Columbia, 1936). She then went on to became most famous for her dancing. Born the oldest of eight children to Philomena Horace Nelson on the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation in Maine, in 1903, she was baptized by a Catholic priest Mary Alice Nelson. Penobscots called her Maliedellis (pronounced MAH-lee-DEL-us), which she

shortened to Molly. Her first public performance was as a child in a local contest, in which she danced an Irish jig. She soon took to learning traditional tribal dances,

earning spare change from tourists to help support her family. Her parents supported the family mostly by selling traditional baskets, her father gathering the natural

materials and her mother weaving them. Horace Nelson went on the serve as tribal chief and the nonvoting Penobscot representative in the Maine State Legislature.

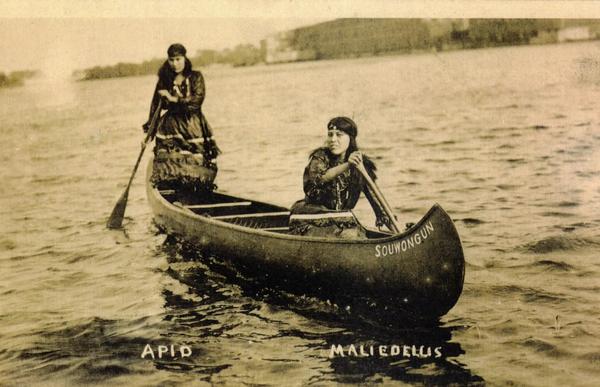

Molly Nelson right, paddling a canoe on the Penobscot River with her sister Apid, 1921. (Raymond H. Fogler Library Special Collections, University of Maine) As a young girl, Molly's mind was already going places. Curious, she questioned tribal elders about the wider world and offered to help with chores if they would tell her tribal legends. “Curiosity killed the cat,” her siblings teased

her. But she left home at age 13 for the opportunity to learn. Living with the family of Frank Speck, a University of Pennsylvania anthropologist, she attended Swarthmore Preparatory School for two years before leaving to join a vaudeville act and send money back to her family. She traveled the wider region with various wild west shows and vaudeville acts, writing and creating her own music and costumes and learning native dances from other tribes, but always felt the pull of home vying with her curiosity about the world. At age 21, on a tour with a company of Indigenous dancers, she found herself in Philadelphia where she reconnected

with the Speck. He arranged for her to audit classes at Penn and she left the tour. The next couple years studied anthropology and literature by day and she scrubbed floors by night. Then she was off to dance again, joining her sister in a wild west show based on a ranch in Oklahoma. She danced, trained to perform on horseback, waited tables, wrote her own music and sewed her own costumes. But Molly

still nursed a dream of fame and fortune and in 1926, she moved to New York City. “Once I become famous, Mama will not have to make any more Indian baskets,” she told a newspaper reporter back home. But in the big city, she found herself "alone, friendless, a hungry innocent Injun girl." Still, she danced. In nightclubs and vaudeville, a dominant form of entertainment in New York City in the 1920s, modeled for artists between auditions and eventually won a spot in the Fosters Girls, a chorus line similar to the Rockettes, which went on the road for an extended run in San Antonio. One journalist wrote that she could perform both traditional and

popular dances with “equal grace.”

Molly Spotted Elk, Public Domain (Wikipedia) Her friendship with a Hollywood producer brought her big break

in 1928, when she was cast in a leading role in The Silent Enemy. Show business, she learned, was "heartbreaking...full of promises, trouble, glamor and rush." Out west, Molly earned minor roles as ‘Princess Spotted Elk’ and lugged around her typewriter between shows to pursue a writing career. In dressing rooms, she wrote poetry, adventure stories, literary fiction

and traditional Penobscot tales. It was disheartening that to capture audience attention, she was forced into stereotypical Native American roles, sometimes wearing a floor-length feathered headdress — and little else.

Nelson in 1928 dressed in one of the outfits she was made to wear to match audiences’ stereotypes of

Native Americans. Credit...via Barbara Moore After Molly sailed for France as the American Indian representative in the ballet corps of the 1931

International Colonial Exposition. that attempted to display the diverse cultures and immense resources of France's colonial possessions. It is estimated that from 7 to 9 million visitors came from over the world.[3] The French government brought people from the colonies to Paris and had them create native arts and crafts and perform in grandly scaled reproductions of their native architectural styles such as huts or temples Europe welcomed the talent Hollywood declined. In Paris, she was happily surprised to find unbigoted, cosmopolitan and enthusiastic audiences for her traditional tribal dances. And she had a chance to use her typewriter

professionally. “She played a dual role,” said her biographer Bunny McBride. “She was on exhibition with other colonized people, yet she

was also an observer who chronicled the event for a major newspaper back home.” After the expo ended and the other members of her group, the United States Indian

Band, returned to the US, Molly stayed.

“Maybe I am foolish, with no money, but hopes galore,” she wrote in her diary. “But I DO want to do something with my Indian dancing here in a serious artistic way. And I’m willing to take a great chance to accomplish

it.”

True to her adventurous spirit, Molly she set off across Europe performing and experiencing new cultures. The Penobscot girl from Indian Island danced

before old World royalty, including King Alphonso of Spain.

Undated photo of Mary Alice Nelson (Molly Spotted Elk) Wherever she went, Molly remained curious and open to learning. Studying at the Sorbonne, she searched dusty archives for documents about the first French contact with the Penobscots. She mingled with artists and intellectuals, gave lecture-recitals at salons and museums and helped support herself teaching ballet in Paris! Her performances were

sensation enough to pique the interest of the city's biggest daily newspaper, Paris Soir. She agreed to meet journalist Jean Archambaud at a sidewalk café for an interview. How do you like Paris, he asked. “It is too loud, I prefer the

woods.” The journalist was smitten. He liked the woods, too, as well as art, literature, history and nature and he was fascinated by her stories of her tribal legends.Within a month he wrote her a love letter: "You are the

guide, a delicious guide for my clumsy footsteps."

Molly Nelson around 1931, the year she performed in Paris, where she lived for several years. Photo: Barbara Moore via New York Times They became lovers, but separated. Molly returned to Los Angeles to work where she gave birth to their a baby girl, also named Jean Archambaud in 1934. For love of Paris or the journalist or both, she returned to Europe, and was soon set to

realize another of her dreams, a book contract for her collection of Penobscot folk tales. Then in September, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and by May marched into France. Despite, or because of, the turmoil Molly and Archambaud married. Her book deal fell through, now the least of her worries. Archambaud, a political journalist, and

director of Red Cross Relief near Bordeaux was an out-spoken anti-Nazi. After the Germans occupied France fell in 1940, he disappeared. Molly and six-year-old Jean escaped on foot across the Pyrenees into Portugal. “We walked, we ran, we rode ambulances,” Jean Moore recalls. “A newsman picked us up once, and my mother always claimed it was Howard K. Smith. Adventure always

followed her, even in adversity.” Molly brought daughter Jean home to Indian Island in July 1940. She didn't know for years the fate of her husband, but eventually learned he had died as a refugee in occupied France in 1941. Dancing on stages across two continents, breaking barriers, and persevering through success and tragedy,

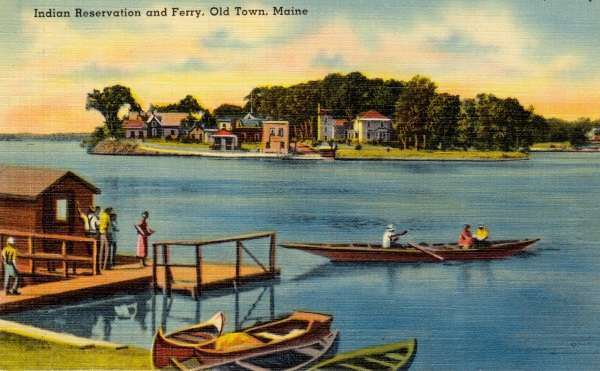

she must have had mixed emotions returning home to Penobscot Indian Island Reservation in Maine and the forests she loved. Molly's biographer wrote the dancer found rural Maine "was like an old pair of moccasins that one dreamed of during years of high-heeled city life—only to find, upon slipping into them, that they felt less comfortable than remembered because the shape of one's

feet had changed."

Postcard, New England Historical Society She continued to write, especially children's stories

based on Penobscot legends, expanding on her original book proposal. "The stories in this book were told to me over and over again by my mother, grandparents and old storytellers of different tribes," she wrote. "I spent many hours picking berries, braiding sweetgrass, weaving baskets, chopping wood or shoveling snow and in return I gathered

many a tale of my people, some old and legendary, and others the product of their own vivid imagination." Molly also crafted Indian dolls in traditional dress, some of which are now in the Smithsonian. Molly's

achievements were singular for any woman in those times, but incredible in how she bridge cultures and dealt with bigotry. Though her dancing has vanished with time, her legacy remains in the story of her life and the stories she wrote. I hope Molly's story brings you as much joy as I had writing it and that some small part of her achievements speaks to your heart and our longing to live life to the full. As always, thank you

for reading. ❤️ I'm honored.

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family and friends.

Sources https://www.penobscotnation.org/departments/cultural-historic-preservation/historic-preservation/molly-spotted-elk/

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|