October 10, 2025 Hello , There's a common thread in conversations I hear these days. People want to "do" something, but they just don't know what. They don't see clear choices. In 2017, I wrote about Cornelia Fort, who didn't like the choices open to women, so she made bold, out-of-the-box choices. My week is busy due to family coming in, so I pulled her story from the archives to

inspire us all. Tell me, If Cornelia had known she would die at twenty-four, would she have chosen the same?

Cornelia Fort: Bold Choices, No Regrets.

Cornelia Clark Fort was born to wealth and privilege, but in the American south in the early 20th Century she was prescribed very narrow role in life. Growing up in a luxurious mansion built in 1815 on the banks of the Cumberland River in Tennessee, she was expected to become a Southern debutante, attend society functions, marry and have children. Cornelia started making improper choices at a young age.

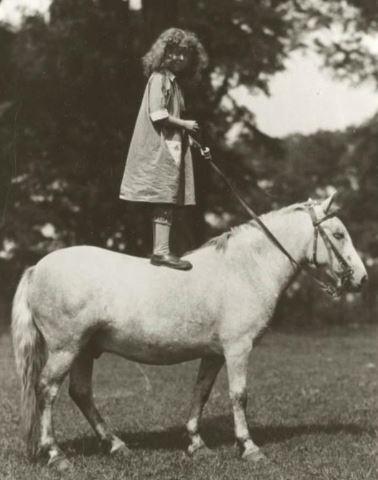

Cornelia Fort as a young girl. Education? Cornelia was sent to Ogontz School for Young Ladies, though she wanted to attend Sarah Lawrence College. Her father at first refused to allow her to apply to that "liberal northern school" where young women could design their own course of study.

Cornelia Fort (Tennessee State Library and

Archives) In her first major rebellion against the "proper" role assigned to her, Cornelia convinced her mother to help change her father's mind. She attended Sarah Lawrence and graduated with a two-year degree. Her next bold move challenging the strictures on women's lives in the 1930s and 40s set Cornelia on a course that led to the skies over Pearl Harbor at the very hour the Japanese attacked. At age five, with her father and three older brothers, Cornelia saw a daring pilot perform acrobatics in the sky. It appeared so dangerous, Dr. Rufus Fort made his sons promise (as one story goes, swear an oath on the family bible) they would never fly. Later, when Cornelia made her first solo flight, one brother chided her for breaking a promise to their father. But Dr. Fort had not thought to ask his daughter not to fly. She was hooked from her very first time in the sky, saying “It gets under your skin, deep down inside.”

Cornelia Fort (with a PT-19A) was a civilian instructor pilot at an airfield near Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. US Air Force Photo. Cornelia Fort became the first female flying instructor in all of Tennessee in 1940. The next year she got a job in Hawaii teaching defense workers, soldiers and sailors to fly.

In November 1941,

Cornelia wrote home (her father had died more than year before). "If I leave here, I will leave the best job that I can have

(unless the national emergency creates a still better one), a very pleasant atmosphere, a good salary, but far the best of all are the planes I fly. Big and fast and better suited for advanced flying. On December 7, 1941, she was in the sky with a student pilot when a small plane nearly collided with them. Cornelia grabbed the controls and saved their lives. “[The plane] passed so close under us that our celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to see what kind of plane it was, she said later. The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.” “Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it down,

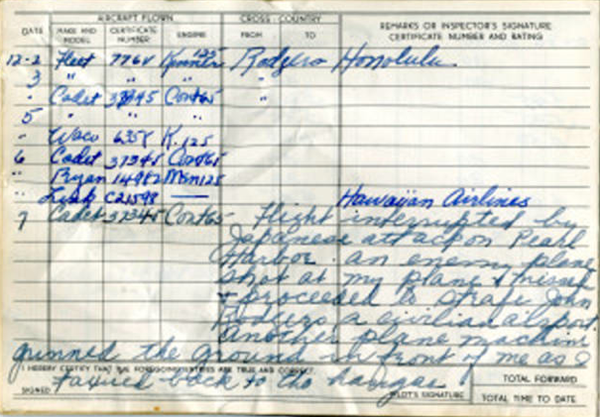

down, and even with knowledge pounding in my mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middle of the harbor. I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a shadow passed over me, and simultaneously bullets spattered all around me.” She wrote about the encounter in her logbook.

Cornelia Fort, an instructor at John Rodgers airport, wrote in her log book for December 7 that the Japanese “shot at my plane & missed.” (U.S. Air

Force) “Later, we counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to

death.” Cornelia survived to step out of bounds again. She knew the risks when she became one of the first to volunteer for Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squad (WAFS) “I felt I could be doing something more

constructive for my country than knitting socks. Better to go to war than lose the things that make life worth living.”

“Because there were so many disbelievers in women pilots, especially in their place in the army....We had to deliver the goods or else. Or else there wouldn’t ever be another chance for

women pilots in any part of the service.”

World War II WAFS stroll past press cameras at New Castle Army Air Force Base,

Delaware. (from left to right): Teresa James, Cornelia Fort, Betty H. Gillies, Aline Rhonie, Helen Mary Clark, Catherine Slocum, Adela Scarr, and Nancy Love. September 1942 (Heritage Flight Museum) The WAFS ferried planes for the U.S. military during WWII, flying them from factories to points of embarkation. The group later merged with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). The women pilots faced painful prejudice from some of the male pilots, who Cornelia said went "to great lengths to discredit them whenever possible.” The

end came quickly, and far to soon. March 21, 1943, flying over Texas in a six-plane formation, Cornelia's Fort's wing tip was clipped by another plane. She crashed to the ground and died instantly.

Cornelia Fort, second from left, poses with several of her fellow female

aviators less than two weeks before her death, 1943. (Nashville Public Library photo) Cornelia was twenty-four, and

became the first female pilot in American history to die in the line of duty, though the WAFS were not recognized as official military service members 1977. I wrote that story here... A year prior to her death, Cornelia had written her mother, poetically describing how much she had loved life, loved green pastures and cities,sunshine on the plains and rain in the mountains, blue jeans, red wine, books, music and the kindness of friends. She ended the letter... If I die violently, who can say it was "before my time"? I should have dearly loved to have had a husband and children. My talents in that line would

have been pretty good but if that was not to be, I want no one to grieve for me. I was happiest in the sky--at dawn when the

quietness of the air was like a caress, when the noon sun beat down and at dusk when the sky was drenched with the fading light. Think of me there and remember me...Love, Cornelia. I have to pause here a moment and take in those words. Cornelia's story reminds me we do not have time to be mired in self-doubt and

indecision. We make the best decisions we can without the benefit of knowing how they will unfold. Like Cornelia, I want to choose boldly and love life hugely, the question is will I? Am I?

Like my article today? Forward this email to share with family

and friends.

Sources https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornelia_Fort

Follow me on social media

This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Read

a great book? Have a burning question? Let me know. If you know someone who might enjoy my newsletter or books, please forward this e-mail. I will never spam you or sell your email address, you can unsubscribe anytime at the link below. To find out more about my books, how I help students, teachers, librarians and writers visit my website at www.MaryCronkFarrell.com. Contact me at MaryCronkFarrell@gmail.com. Click here to subscribe to this newsletter. |

|

|